3. How to judge contemporary art

The controversies around the value of contemporary art always revolve around aesthetic criteria. Each artistic practice obeys more or less explicit rules from which it is possible to evaluate the excellence of the artworks. The problem that arises from the considerable variation in artistic practices in contemporary art is that there are too many criteria and, therefore, there are no legitimate criteria codified according to a scale of the general canon. In the second part of my research, I will therefore examine how one can account for the criteria of the judgment of taste under the condition of an aesthetic unity of contemporary works of art. We then move on to the aesthetic pluralism of Yves Michaud who takes up and develops the reflections of Hume by placing them in the Wittgensteinian conceptual framework.

The pluralist aesthetic of Yves Michaud

The essay by philosopher Yves Michaud devoted to Aesthetic criteria and the judgment of taste offers the methodological keys for the rationalization of the era of art of “anything”. Michaud begins his debate on aesthetic criteria by allaying the concerns of skeptics of contemporary art. From the 90s, critics either question the existence of art or claim that there is no crisis in contemporary art and nothing to discuss. The frequent and not unfounded reasoning is that we cannot yet judge contemporary art since there are no longer valid aesthetic criteria (1). Anything can therefore be art and everything is worth it. Watching Boltansky’s Reliquaire les Linges, the skeptical viewer can smile mischievously and imagine himself as the creator of this work (2).

Indeed, all the elements of this installation are ordinary and accessible: black and white photos of children, piled up colorful clothes, a mesh metal box, neon lighting. The viewer nostalgic for the fine arts would also be frustrated by the value of artistic production reducing the work to a concept. Even if it is an expensive artistic work, which can be observed in the gigantic exhibition of Christo and Jeanne-Claude Surrounded Islands, it does not save the situation (3). This artwork can in any case be devalued by the cynical opinion that this object of art is successful precisely thanks to its large scale and the material resources of the realization. The detractor would say that any wealthy person can circle Miami’s Biscayne Bay Islands with a belt of hot pink polypropylene. However, this reasoning often leads to the cessation of discussion on art as such, when the situation requires another approach.

To reflect on the question of the disappearance of aesthetic criteria, it is first necessary to specify what is a criterion. When we say that we are applying a criterion, we are making the distinction between things, people or notions. Depending on the aesthetic criterion, artistic productions are distinguished. They are chosen or not for exhibition, sale, research, etc. If we find that there are no more valid aesthetic criteria, we accept an absence of the means to make distinctions (4). Finding criteria would mean marking the differences between contemporary art objects and appreciating their qualities.

According to Michaud, the debate on the end of art is not justified since the history of art is absolutely not linear. Art can always change paths and is defined differently according to times and places. What we observe today is a new era of postmodernity, where the proliferation of artistic forms and experiences has completed the cultural hegemony of the fine arts (5). The definition of art has changed, but galleries or museums continue to exhibit works of contemporary art under the same unified notion of fine arts, that of ideal beauty (6). Indeed, it is difficult to understand what there is in common between artworks that arouse feelings of pleasure, boredom, repulsion, sensuality or intellectual satisfaction.

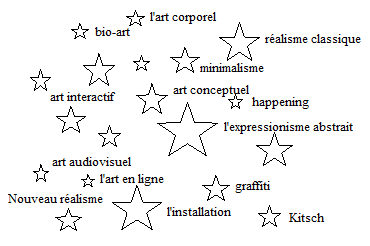

The artistic plurality devoid of coherence and organization actually reveals the art of “anything”. It has become clear that almost anything is possible in artistic practice (7). The art world forms new hierarchies of values, but is incapable of bringing this immense difference of valuation to a general scale. We can imagine that the stars that we see in the night sky represent the multiple hierarchies of contemporary works of art grouped into artistic practices.

We therefore observe the stars of conceptual art, abstract expressionism, happening, installation, minimalism, pop art, neo-dadaism, robotic art, graffiti art , body art, line art, classical realism, traditional African art and many more. Each star is a stand-alone art value that holds for a certain group or individual. New works of art either join a hierarchy present under certain conditions of group acceptance, or form a new hierarchy of value, i.e. a star.

The difficulty of contemporary art is thus to think of the plurality of values but in a conceptually organized and unified way. Aesthetic unity requires getting out of a strictly relativistic attitude, but the plurality of the arts without relativism is not possible. To explain the diversity of judgments, Michaud posits aesthetic value as a secondary quality, like Locke’s secondary quality. It follows that the properties of a work of art are dependent on the psychological properties of the human being, that is to say that judgments of aesthetic values would only be subjective expressions of the individual. However, Michaud is far from a subjectivist position. On the one hand, value is produced by artistic qualities imposed on the object; on the other hand, it is given in a perceptual experience. As the experience of evaluation is correlative to the work and similar in all human beings, value is conceived as an objective cause of this experience (8).

What distinguishes Michaud’s objectivism from the realist position is a relativization of evaluations in each local group of experience. In other words, the spectator’s perception relativizes this objectivism by entering into the language game. For example, Tulips by Koons has value only for a particular group or person who has a particular experience of this work (9). If I tried to appreciate it, I would have no choice but to enter the language game of pop art and learn its criteria.

Then, the value is a value relative to pop art posing an authority to which other spectators can conform. This conformity consists in supporting the acceptance of relativism, since particular values are objectively inscribed in the works of contemporary artists.

In the case of the ready-made, it is the artist-spectator couple who make the works. If the spectators contributed to the creation of a work of art, as Duchamp claimed, one could not escape the complete relativism of taste and each could express the claims of his or her own subjectivity (10). However, concordance between the two sets of qualities is not guaranteed. Taste as a result of learning is not innate or natural. It is shaped from the evaluation language game (11). The true aesthetic experience is a convergence between a desired effect and a certain artistic quality. If the desired effect does not occur, either the viewer is unable to perceive it or there is an absence of this effect. If the effect produced is not the intended effect, the viewer may be misunderstood about the effects. However, the lack of correspondence between the judgment of taste and the artistic qualities in the object always leads to an erroneous judgment. This may explain the case where someone finds the Mona Lisa to be primitive or, on the contrary, an inventive cliche. It is also possible to evaluate works without regard to their artistic qualities, but this corresponds more to the way of relating to dated art than to a general definition of art.

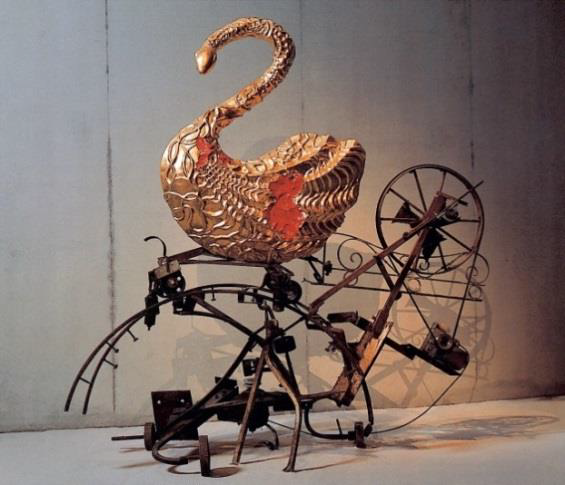

It follows that the process of aesthetic judgment is learning to match an appropriate reaction to appropriate qualities (12). The mastery of artistic rules and the mastery of the response to contemporary works of art is the lesson of the experience that everyone can get as education and evolve his or her personal taste. It is standardized through complex learning that includes comparison, experience, intervention of others’ points of view (13). However, this double process of education and elaboration which operates on the artistic qualities and on the aesthetic experience seems problematic. The skeptic would point out that one cannot attune the full variety of canon-defined aesthetic experiences to such canonically established artistic qualities. The difficulty that arises is how to match, for example, the experience of perceiving an immersive environment by James Turell with that of perceiving a mechanical sculpture by Jean Tinguely.

How to unify all the diversity of aesthetic responses to the diversity of works of art? In response to this, Michaud calls for thinking about aesthetic experience in the context of a family of experiences that have family resemblances between them (14). In the situation of pluralism that we live in, we find that the various aesthetic experiences of art objects can be identical or similar. Even if we are interested in different aspects such as the motivation of the artist, the traces of history or the technical success, the criteria that we value are universally applicable to an immense variety of art objects. They are based not on the fundamental agreement of sensitivities but on their continually renewed effort to agree (15).

The plurality of knowers does not impose on relativism a criterion of absolute universality because the experience internal to a language game does not have to be exported outside of this game. What is called the truth of an evaluation statement does not need to be proven outside of this game (16). For example, the Mona Lisa and the ready-made are high values in the categories of the aesthetic evaluation, but they belong to different areas of appreciation. It is thus useless to note that the Mona Lisa is beautiful as a readymade and vice versa. However, Michaud admits that one can always try to widen the agreements on the common criteria of the judgment of taste. This involves changing the language game by imposing values that will combine a set of value hierarchies. Returning to our image of the night sky, these combinations of values would be like assemblages of stars, namely constellations. There is no unifying whole while it is absolutely unified. What makes the unity of each criterion as an evaluation scale is a network or cross-belonging.

The question that arises is to know which canon the hierarchies of values could obey. By the canon, these are the explicit traits from which it is possible to evaluate the excellence of the productions. According to Michaud, these can be physical properties as well as non-physical qualities of the art object. Some works have in common the correctness and exactness in the repetition, the fidelity of resemblance, the capacity to function as a “monument” and many others (17). In this sense, an American abstract expressionist painting from the 1950s and a work of decorative art can belong to the same “galaxy of values”, since the well-repeated is part of these artistic qualities. Similarly, the work of Buren and that of Boltanski have in common the way in which they proliferate by repeating themselves (18). The resemblance or the well-imitated is also a value that can include the variety of contemporary works such as Banski’s graffiti, the sculpture of Ron Mueck and a canvas by Zhang Xiaogang.

There is a main question to be addressed here. Michaud asks “…what causes certain appreciations and forms of language to be better shared, more universally and more durably shared, while others will remain localized or pass quickly” (19). However, Michaud wants to posit a principle of aesthetic experience that not only agrees with the universal character, but is also likely to be susceptible to varying degrees on scales of appreciation. According to him, the differences in degrees in the aesthetic experience can be due to several reasons. First, we must recognize the effects of cultural domination that imposes standards of life and representation (20). While in the 19th century there was a cultural domination of romantic ideas, in the 20th century we came to the domination of abstract expressionism, pop art, Hollywood film. Second, the degree of appreciation can be correlated to the artistic object. In other words, there are certain art forms that are more susceptible to universal reception than others. We can admit, for example, that the language game of the aesthetic appreciation of fine art is more accessible and better shared than that of conceptual art. According to Sibley’s meta-critical position, this complexity of the appreciation of contemporary art objects compared to that of the fine arts can be explained by the insufficiency of the non-aesthetic criteria on which our aesthetic appreciation is based. This may be the reason why I am much more lost in front of the installation of Joseph Beuys than in front of the expressionist painting The Scream by Edvard Munch (21). The Scream is easily deciphered by the distortion of brushstrokes, color intensity and spiritual connection while Tisch mit Aggregat involves the puzzle of understanding a concept. Then there are misunderstandings of language game appreciation. One can mark not only the differences between the language games but also the misunderstandings within the same game. Here, Michaud refers to the “Mona Lisa problem” according to which there is a huge discrepancy on the reasons that make this painting by Leonardo da Vinci a masterpiece. Someone is admired by Mona Lisa`s smile, a symbol of quiet happiness or by the da Vinci technique “sfumato” highlighting the effects of shadow and light on the face of the Mona Lisa. Another viewer can enjoy her mysterious eyes following us from any angle. It happens that the aesthetic effect produced is the same, but the reason for this effect is different. Finally, there is the successful condition of the language game in the sense of expanding the game through reviews, exhibitions, publications, exchanges, press, etc. (22). The power effect of the language game therefore increases through persuasion of new members or widening of agreements. As a result, this process leads to a change in the language game, “because giving orders and knowing how to obey them is also a language game” (23). Here we fall into the field of constant interactions that require new aesthetic, local and relative criteria.

This new paradigm of aesthetic pluralism that Michaud defends is harshly criticized by Marc Jimenez in La querelle de l’art contemporain (24). First of all, Jimenez points out that the recurring concepts of this thought inspired by analytical philosophy lead to the disqualification of the value judgment, and, paradoxically, of the criteria of evaluation in social terms. Philosophers question diversity, subjectivism, relativism, while the paradigm of cultural pluralism ignores the basis of any reflection on the organization and functioning of current society. It is as if our political, economic and cultural system authorized an extreme diversification of artistic practices which leads to the diversity of aesthetic experiences. It promotes democratic judgment where everyone makes their own assessments less and less subject to authoritarian standards of taste. Simultaneously, this same system makes the individual “…a passive consumer, subject to institutional, industrial, economic, communicational and technological strategies and constraints which are applied massively, while the individual has not right to say a word” (25). Ultimately, the aesthetics of pluralism defines art only institutionally, while neglecting art in the social and cultural context. Therefore, the new model of interpreting art returns to a generalized and abstract thought that is far from everyday life.

To counter this criticism, it must be recognized that Michaud does not intentionally accept pure and simple aesthetic judgments made by competent social groups (26). In one particular society, for example, men revere Jeff Koons. In another, they recognize only impressionist works. It then becomes a fact that there is a sharing of canons between different groups, but this distinction mastered by the sociologist does not constitute a problem for philosophical reflection. In its noble form, this position takes the diversity of contemporary art in general as an immeasurable act and, therefore, it departs from the nature of aesthetics. Conversely, Michaud evokes the questions concerning the consensus within the world of art at a time of the disappearance or the invisibility of legitimate aesthetic criteria. His project is to find universal ways in which man can share experience among different societies and cultures. Even if Michaud sometimes omits concrete case analysis, he shows us a theoretical path that allows us to adapt his aesthetic discourse to the unprecedented situation. In the next chapter, I will therefore try to develop his idea of the aesthetics of pluralism from the particular examples. It is a diagram of unity and homogeneity of the art of “anything” in its practical application.

References:

(1) Yves MICHAUD, Critères esthétique et jugement de goût, op. cit., p.8.

(2) Christian Boltanski, Reliquaire, les Linges, 1996.

(3) Christo et Jeanne-Claude, Surrounded Islands, 1983. See http://christojeanneclaude.net/mobile/projects?p=surrounded-islands#.VJFv-NLF9Zo.

(4) Yves MICHAUD, Critères esthétique et jugement de goût, op. cit., p.51.

(5) Ibid. 10.

(6) Ibid. 28.

(7) Ibid. 26.

(8) Yves MICHAUD, Critères esthétique et jugement de goût, op. cit., 18.

(9) Jeff Koons, Tulips, 1995-2004, Guggenheim Bilbao Museoa. Voir http://europaenfotos.com/vizcaya/pho_bilbo_16.html.

(10) Yves MICHAUD, Critères esthétique et jugement de goût, op. cit., p.38.

(11) Ibid. 40.

(12) Ibid. 39.

(13) Ibid. 46.

(14) Yves MICHAUD, Critères esthétique et jugement de goût, op. cit., 41.

(15) Ibid. 89.

(16) Ibid. 20.

(17) Ibid. 32.

(18) It is about Personnes de Boltanski (2010) and Les Deux Plateaux de Daniel Buren (1985-1986).

(19) Yves MICHAUD, Critères esthétique et jugement de goût, op. cit., p. 91-92.

(20) Ibid.

(21) I compare an artwork by Edvard Munch The Scream (1893) with an artwork of Joseph Beuys Tisch mit Aggregat (1958–85).

(22) Yves MICHAUD, Critères esthétique et jugement de goût, op. cit., 93-95.

(23) Ibid.

(24) Marc JIMENEZ, La Querelle de l’art contemporain, op. cit., p. 235-236.

(25) Ibid. p. 236.

(26) Yves MICHAUD, Critères esthétiques et jugement de goût, op. cit., p.57.