2. Ruptures of contemporary art

Appearing after the Second World War, with Marcel Duchamp as a precursor, contemporary art is often unrecognized or misunderstood. It leaves no one indifferent, arousing passion, perplexity or contempt, sometimes going so far as to question its legitimacy. By presenting itself as an experimental art, contemporary art transgresses rules in perpetual innovation. It seeks a rupture with traditional art, as with any previous creation. Among the latest truly daring innovations, we can cite “body art” which consists of a performance centered on the body, with sometimes experiments bordering on masochism (Burden, Nebreda); “biotech” art which places itself in anticipation and prophecy (Sterlac, Kurtz); or conceptual art, which substitutes the idea of an artwork for the finished work (1). It aims for the “deconstruction” of art (monochromes by Malevitch, ready-mades by Duchamp), going so far as to question painting itself.

Little by little, the academic tradition is abandoned and conventional artist’s techniques are questioned. Deprived of their traditional artistic markers, viewers try to rely on aesthetic criteria to judge contemporary art as they did it for traditional art. However, the main purpose of contemporary art is no longer precisely to represent or even present beauty, since it often advocates aesthetic detachment. This is how we come to reproach this art for being “boring”, “without content”, “without talent”, even for concealing a great void with “intellectual lucubrations” or “trickers”. To tell the truth, it is even difficult for the spectator to imagine how objects, so banal, could give him or her a sensory pleasure, whatever their staging. The fundamental notion of art as a source of emotions is therefore called into question. Contemporary art appears rather to be reserved for the initiated.

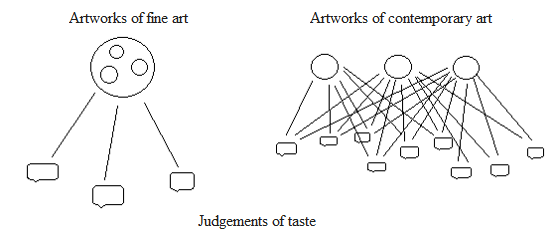

By upsetting the frames to the point that it is now difficult to distinguish what is art from what is not, contemporary art has therefore cut itself off from the public. Under these conditions, the aesthetic experience of the viewer is disrupted and the artistic criteria are broken. The challenge of our project is then to determine what specifically makes the difference between contemporary art and traditional art. The ruptures that we are looking for will not only show us the reasons for misunderstanding contemporary art, but also help us to differentiate it within the same concept as contemporary art. This differentiation would make it possible to rethink the aesthetic valuation that falsely claimed the unity of art and, on this basis, to build new scales of appreciation.

Considering aesthetic experience as a double process of elaboration that operates on the descriptive qualities and on the aesthetic qualities of an art object, it is reasonable to illuminate the ruptures in the context of these two domains of experience. In my research, I will therefore rely on the canonical positions of the judgment of taste of Kant, Hume, Sibley and other philosophers to identify what complicates our aesthetic judgment of contemporary art.

Kant’s judgment of taste

Kant’s point, through the concepts of aesthetic common sense and disinterestedness, is perhaps not satisfactory today. However, his project was an alternative to aesthetic objectivism at the time of the emergence of an art audience and putting in place of the relativity of the judgment of taste. By giving way to natural taste, Kant claimed to achieve an objectivism that relies on transcendental subjectivity. In our era of aesthetic relativism, it seems useful to look at the origins of the phenomenon of Kantian taste since Kant was the first to try to think about pluralism of taste without referring to taste monopolized by a dominant social group. On the other hand, Kant wanted to avoid the trap of relativism by updating objective rankings. The concept of aesthetics appeared in 1715 when Baumgarten founded the science of sensory knowledge under this name. His idea of an aesthetic rationality consists in subjecting the critical judgment of beauty to rational principles. In other words, Baumgarten wants to establish a synthesis between art and science, a tool for the spectator as well as for the artist. This science would sometimes make it possible to execute and sometimes to judge with more certainty and assurance the works that claim to be beautiful in thought. Kant absolutely rejects it saying that:

These rules or criteria, in fact, as to their main sources, are simply empirical and can never, therefore, serve as determined a priori laws on which our aesthetic judgment should be based (2).

Kant therefore renounces all the rationality of aesthetic judgment since the judgment of taste does not concern the object in its objective reality. It follows that the aesthetic nature is merely subjective in the representation of an object.

In this regard, Kant adds that the judgment of taste, being subjective, necessarily passes from the point of view of its claim for an objective judgment. I don’t say, for example, “I like it”, but “it’s beautiful”. I claim that everyone finds it beautiful. Contrary to Kant, La Rochefoucauld announces the non-universality of the judgment of taste since it is a judgment that distinguishes one from the others (3). Similarly, Baudelaire emphasizes that the judgment of taste is a judgment of distinction between groups and “it’s beautiful” claims validity within a group. If the judgment of taste is absolutely singular, how can one simultaneously universalize its experience in Kant? Kant rejects any argument likely to carry the conviction of others, because it is not based on anything other than the pleasure felt in front of the beautiful object. The beautiful is what pleases us universally without a concept and, therefore, it cannot be justified by concepts. For Jacqueline Lichtenstein, what makes our aesthetic experience shared is the fact of speaking (4). Indeed, language allows us to get out of this Kantian difficulty. From the moment I express “it’s beautiful” in a proposal, it becomes a public, communicable and proven experience. The word creates the thought in the sense that it produces the object of which it speaks. When I speak, for example, of the Mona Lisa, the emotion that I express is no longer quite the first emotion that I felt when looking at the painting. From the moment we begin to say this emotion, it differentiates and becomes more subtle. It can be compared with other forms of emotions and, by this differentiation, the name becomes the named emotion.

The question that arises is to know on what is based such a judgment. Can we convince others of the beauty or the ugliness of an object? In Kant, the assent of others is not sufficient proof of the validity of the judgment. There is no empirical evidence to impose the judgment of taste on someone. Such a judgment is based on the satisfaction experienced in the presence of the beautiful object. By saying “it’s beautiful”, I say my pleasure in contemplating the object. This pleasure, maintains Kant, is not the cause but the effect of the feeling of the universal communicability of the state of mind (5). In §9 of the Critique of Judgment, Kant writes:

The universal subjective communicability of representations in a judgment of taste, which must occur without assuming a determined concept, cannot be anything other than the state of mind resulting from the free play of the imagination and the understanding (6) .

In this case, the claim to subjective universality is only an adherence to the natural harmony, not based on concepts, which must be valid for everyone and which determines the feeling of pleasure. In aesthetic experience, sensitivity and intelligence, imagination and understanding are in harmony. Kant defines this harmony as free play of the faculties or free agreement. It follows that the object must contain a principle of satisfaction for all, that of transcendental subjectivity. In other words, when I say “it’s beautiful”, I believe that it is possible to form a judgment capable of requiring such assent universally. Within the framework of an aesthetic common sense, what is valid for only one is worth nothing. We do not say “this is beautiful for me”, but pretend that this thing is beautiful for everyone. We can therefore define taste as the faculty of judging, an ideal norm universally communicable without the mediation of a concept.

My judgment of taste is therefore not a judgment of knowledge, since it does not provide information on the objective qualities of the object. In the well-known passage §1 of the Critique of Judgment, Kant writes:

To distinguish whether a thing is beautiful or not, we do not relate to the object by means of the understanding the representation in view of a knowledge, but we relate to it by the imagination (perhaps linked to the understanding) about it and by the feeling of pleasure and pain of it. The judgment of taste is therefore not a judgment of knowledge (7).

Here, Kant declares that the judgment of taste is not a judgment of knowledge, but a reflective judgment. If I say, for example, that Cloud Gate by Anish Kapoor is beautiful, I am not giving any information about this sculpture. The beautiful predicate does not return any property of the object. It is not a false judgment, but a judgment which expresses the subject’s attitude towards an object.

To say that aesthetic judgment is only a pseudo-act of knowledge goes against the idea generally held at the time that knowledge is a part of the judgment of taste. In the Middle Ages, cathedrals were spoken of as architectural beauties. Their clarity, for example, was one of the criteria of their beauty. In other words, there was a consensus that beauty is occasioned by properties that exist in the beautiful object. It is obvious that today this consensus is entirely broken. There is no general agreement on the property that allows us to base the aesthetic judgment. The disagreement is particularly aggravated by contemporary art since the discernment of the aesthetic qualities, for example, of a conceptual work, becomes an impossible task.

In the 17th century, La Rochefoucauld like many other contemporary philosophers gave a double meaning to the judgment of taste. On the one hand, there is taste as a preference “which leads us towards things” (8). To this apply desire, feelings of pleasure, love. On the other side, there is taste as knowledge, discernment. It is an act of reason. To have fine and delicate taste means to discern the qualities of things, but this knowledge is not enough. For La Rochefoucauld, taste contains desire as well as discernment. This idea is basically very old since we find this synthesis between reason and pleasure, between the rational act and preference in Antiquity.

We see that this second meaning of the word taste will disappear in aesthetic judgment from Kant onwards. Unlike the descriptive judgment which describes a property of the object, the aesthetic judgment does not exist independently of us. It therefore belongs to a class of judgments called the value judgment. If I say that a thing is beautiful, I express the hierarchy of desirable things. Traditionally, the realm of feelings is said to be the realm of value which is subjective and relative. The value depends on the value system that performs the evaluation procedure. Value predicates such as gracious, expensive, good, are just introduced as descriptive properties, but in fact they are not properties that belong to objects. These are relational properties that imply a relationship between the subject and the object. The evaluation of an artwork determines the value by examination, while the valuation is a matter of fashion or of the market. Today, the aesthetic value of a work of art is totally independent of the material, of the time spent, of all that intervenes in the determination of the value. To know why one work of contemporary art is superior to another, the work of evaluation is essential, since it constitutes art criticism. If we value a work without evaluation, we abolish all criticism.

In Kant, the beautiful should not be confused with the useful, because the useful implies knowledge of the object. If the beautiful does not depend on any determined concept, the pleasure it gives is pure of all interest. An interested judgment is a judgment that is interested in the existence of the object. An aesthetic judgment is therefore a judgment that is not interested in the existence of the object but only in its representation. In his introduction to aesthetics, Hegel takes up this idea of disinterested judgment, but he speaks of the analysis of desire (9). Aesthetic experience necessarily involves a frustrated desire, namely a private desire for satisfaction. Hegel distinguishes artistic interest from practical interest in that artistic interest allows its object to subsist. I have a practical interest when I eat an apple, while I let Monet’s still life remain which gives me aesthetic pleasure. On the other hand, artistic interest differs from theoretical interest in the sense that it is interested in the object in its singularity. In other words, the artistic interest is the spiritual and singular interest, while the object of a scientific interest is a general, generic or universal object. The aesthetic relation therefore implies an interest, but an interest that is not practical like a desire, nor purely theoretical like in science.

Kant asks us not to dispute taste, because it is not based on empirical or rational evidence. It follows that a universal rule according to which one could objectively determine beauty is meaningless. What constitutes our aesthetic judgment is a feeling of satisfaction which is always singular. In this personal experience, the sensation of pleasure postulates the possibility of an aesthetic judgment that can be valid at the same time for everyone. Such universal assent refers to an aesthetic common sense which is neither cognitive nor logical, but which is communicable a priori. In his book The Crisis of Contemporary Art, Yves Michaud interprets Kant’s aesthetic common sense as a utopia of a common world (10). The Kantian concern to found the universality of the judgment of taste by respecting the singular judgment is the problem of modernity. At that time, art entered the public sphere which generated the aesthetic question. Man claims the right to freely determine the criteria of taste. By adapting to this historical moment, Kant tries to invent the art of communication which would unify ideas of the most cultivated and the most uneducated classes. He denounces art as an instrument of social distinction and introduces cultural equality as a civic utopia. To a certain extent, Kant’s point was prophetic, because the cultural utopia of modernity was realized in a postmodernity. On the other hand, sociological criticism tells us that the determination of the entirely subjective and objectively transcendental judgment of taste leads art to aesthetic anarchy. Every judgement is valid since everyone has their own taste, based on a common aesthetic sense. Yet where is the universal?

In defending the idea of art in its classical form, Pierre Bourdieu criticizes Kant for his stigmatization of refined taste (11). By abandoning the taste of the privileged class, society no longer has a point of reference for legitimate and determining taste. If we want to found an aesthetic common sense in a Kantian way, we must admit that the great classical works would only be the expression of the arbitrary taste of a social class. How could we understand that the man of the 20th century is touched by an artwork of classical Greece? Should we not consider that the universality of the judgment of taste must be based on education around great artworks? In La distinction, Bourdieu seeks to relativize the analysis of the Critique of the Faculty of Judgment to show the differentiation of the judgment of taste, by being inherent in social relations. We must not therefore believe that to distinguish the beautiful from the ugly it is enough to base our judgment on the state of mind that leads us towards natural harmony.

The Kantian interpretation of art does not allow us to take contemporary works of art seriously. Looking, for example, at a work by Christopher Wool, we are unable to pass our judgment of taste on the sensation or the expression of ourselves. In this case, it is necessary to report on the conceptual dimension of a work of art in the name of a pleasure sublimated by intelligence. Reestablishing Kantian sensibility would therefore mean accepting the principle of an art that breaks with the principle of expression of 20th century art. In Subversion and Subvention, Rainer Rochlitz adds that if it is pure desire that most intimately founds the judgment of taste, how to distinguish between the pornographic image and The Origin of the World by Gustave Courbet excluding intellectual articulations? (12) The Kantian question of whether judgment is inside of aesthetic pleasure is meaningless, because there is no primary access to aesthetic pleasure. Finally, if we exclude all objective properties in the definition of beauty, the critic cannot describe a work of art in a neutral way either. It is impossible to claim to aesthetic value without postulating an objective property in the artistic object. Therefore, an object, a text or an image as the elements of a work cannot be grasped as aesthetic objects. As Rochlitz says, an artwork that is not interpreted or evaluated is dead (13). Unlike the judgment on a natural object, the artist expects a judgment from us. Therefore, a work of art depends on an appreciation insofar as it responds to a constitutive rational requirement of the object. Even though these reasons cannot force us to take pleasure in a particular work, they can nevertheless cause us to recognize a judgment according to which an artwork is successful. I can, for example, give someone reasons why Francis Bacon’s Tryptique can be considered a successful work. My reasoning would be based on the description of the unique technique that Bacon used in making this painting. At the same time, this artwork does not please me visually since it seems repulsive, cruel and terrifying. The same meaning of taste is already in La Rochefoucauld who underlines “…that one can have good enough taste to judge comedy well without liking it” (14). In this case, taste contains both senses: attraction and knowledge. If we escape taste as knowledge that postulates a property within a work of art, we present taste as purely sensory, outside of memory and outside of criticism.

To conclude, Kant points to a reflexive judgment that does not presuppose any pre-established rule. Even if Kant determines the object of knowledge by the scientific concept, he relates also to the “suprasensible” or the absolute. Once the judgment of taste was differentiated from that of knowledge, the ambiguity of this aesthetic sphere opened the door either to irrationalism or to a new dogmatic rationalism (15). In this case, if we want to abstain from the absolute irreducibility of the artistic phenomenon, we must rely on aesthetic rationality which admits the justification of judgments by argumentation.

Hume’s judgment of taste

Hume’s theory of judgment of taste seems to escape the reductionisms of aesthetic theories since Romanticism. Hume, as an empiricist, accepts that there is a great diversity of tastes. However, he does not seek the principle of absolute equality of tastes according to Kant’s approach. For Hume, to each his own taste, but not to the point of saying that each judgment is valid (16). He therefore distinguishes between qualified judgment and bad judgment. Qualified judgment refers to the sharp judgment of human taste in perfect circumstances. It is an ultimate agreement on a feeling of man produced by a quality of the object and by a pre-established agreement of the object with human nature. Hume points out that this unique concordance between object and man is rare since the natural constitution of each gives him his individual mood and disposition. A degree of variation is also caused by opinions specific to each era and each society. On the other hand, the opinion of the experts concerns the state of perfection of the internal and external sensation. In other words, in the experience of standardized taste, there is the absence of prejudice and the right disposition appropriate to the object. The sharpness of perception consists in concentration, comparison, attention, consideration of all the components of the object from various angles. It follows that Hume, unlike Kant, admits knowledge in the judgment of taste since there is room for a practice of standardized taste education. This leads to the conclusion that aesthetic appreciation is neither immediate nor easy, and requires finesse of discernment.

What is called Kant’s judgment of taste is described as Hume’s feeling. It is always subjective, because it does not refer to anything beyond itself. Any sentiment of the beautiful is just since it in no way represents their object. Now, beauty is only the suitability of the object to the organ. However, as soon as man refers to something beyond sensation, he refers to the understanding or the judgment of taste. For a thousand judgments, “…there is one, and one only, that is just and true; the only difficulty is to determine it and to make it certain” (17). It is therefore observed that there are certain qualities in works of art which naturally cause a feeling of pleasure.

In this context, Hume refers to masterpieces which, despite changes in climate, government, religion or language, still remain objects admired by different societies. Although we can see a complete uniformity of feelings, the feeling of pleasure aroused by a masterpiece does not mean that the judgment of taste must necessarily be right. Beyond the quality of the object which naturally pleases, there are other qualities which can produce a pleasure, but which do not represent true value factors. It follows that the judgment of Humean taste can be subjective as well as objective. The subjective judgment is a judgment inappropriate to the existence of a quality which pleases universally, whereas the objective judgment more or less approaches a standard of experience which would naturally unite all the circumstances. We thus have a rule of taste as a model definable by external and internal circumstances. On the one hand, this model rests on the feeling which approves or blames by pleasure or pain. On the other hand, this model acquires authority through the descriptive criteria used. Now, the perfection of the organ of perception and the perfection of the work of art perceived constitute the value of a work as a whole.

Hume does mean that human nature is universal in that pleasure and pain are common to all men (18). From this follows this argument that certain qualities of objects can universally cause the feeling of Beauty. If every man is capable of praise and blame, it means that the human mind is endowed with the universal algorithm for the appreciation of the qualities of the object. If the object possesses certain qualities which arouse pleasure in one of the spectators, they must naturally arouse the same pleasure in other spectators. However, Hume makes a distinction between natural universality and formal universality. Unlike formal universality which is abstract and empty of content, natural universality depends on circumstances. The reason for the variety of the judgment of taste is therefore the different circumstances under which men judge works of art.

For this reason, Hume does not see in an immediate appreciation a real judgment since it does not represent the knowledge of the causes of the feeling of the Beautiful. He recognizes that natural circumstances must be brought together in the judgment of taste by means of reason. We can unify all the works by saying that there is a standard in the world of art and in this standard is expressed a common sense to all men. If men shared the same individual temperament and social condition, their judgments of taste might be identical, for men inherit the same nature. Like Kant, Hume establishes the universal principle which stems from a natural affection acting in every man. Yet he introduces the rules of taste judgment to balance the plurality of taste judgments influenced by variations in culture and personal circumstances. While Kant does not distinguish between good judgment and bad judgment, Hume introduces the hierarchy of taste judgments that results from rational activity. In this respect, the application of the universal rule for all works of art seems problematic today taking into account the immense variety of artistic productions. Can we, for example, classify works of performance art, ready-made art and urban art under the same hierarchy of values? How to universally judge these artworks so different, but strongly valid in each local group of experts? Hume keeps talking about the degree of perfection of the perceived work, but defining a degree of perfection of contemporary works of art poses a problem. These varied arts reflect artistic creation, each with its own mediums and criteria of perfection. We appreciate, for example, the beauty of urban art by the harmony that represents the enriching union between the work and the public space. The ready-made leads us to appreciate the concept of a work, while performance art relies on the notion of the effectiveness of an action in the process of happening, and on the immediacy of its signifying power. To this variety of artistic standards is added the difficulty of identifying the criteria for an aesthetic appreciation of contemporary works that represent a mixture of genres. One of the examples of this eclectic mix would be the exhibition Silence and Slow Time by Catherine Widgery which goes beyond the particular practice or technique (19). Apart from everyday objects, this artist plays with light, textures, shapes trying to create a new dimension of the visual image that unifies the structure of the human world with the beauty of the natural environment. Although the aesthetic feelings of men approach more or less a standard, the criteria of the judgment of taste are dispersed between individuals when they have to judge the value of a work. Hume’s standardized taste therefore leads to an indeterminacy, that of the general value of Beauty, which would represent all degrees of appreciation in aesthetic judgment.

Sibley’s aesthetic concepts

When we make a judgment, we use a large number of terms to justify our aesthetic appreciation. Looking at a painting that we like or dislike, we are not content to simply say “it’s beautiful” or “it’s ugly”. On the one hand, we mark the physical features of the object by saying that a painting uses bright colors, that a texture is vague or the lines are curved. On the other hand, we use words that require taste: garish, lively, banal, delicate, graceful, elegant. The first are non-aesthetic and objective traits, which are imposed on the subject by the simple perception of the object, while the second, which we will call aesthetic concepts, come from an aesthetic sensibility. The question that arises is how one applies aesthetic concepts. Are there any rules for this application? Within the framework of Sibley’s analysis, I will wonder about the reasons for the rupture between the judgment of taste of traditional art and that of contemporary art.

In “Aesthetic concepts”, Franc Sibley reflects on the relationship between aesthetic and non-aesthetic concepts (20). He notes that in order to support our application of an aesthetic term, we refer to descriptive traits. We say, for example, that “this painting is inventive thanks to its unusual texture” or “this installation is shocking because of the bloody images”. If I say “this painting is beautiful because it is graceful”, my value judgment is not based on a judgment of fact. To go from fact to value we have to rely on descriptive statements that describe a property of the object. Such propositions are susceptible of truth or falsity since I can put my finger on a quality which strikes me as being the correct explanation. It follows that aesthetic qualities always require non-aesthetic qualities to be legitimate. Otherwise, the existence of the non-aesthetic trait is a necessary condition for the application of the aesthetic concept.

In this regard, one may wonder whether there are a sufficient number of relevant traits for the application of the concept. Sibley examines the following case: if the vase is pale pink, a little curved, slightly marbled, are these traits enough to say that the vase can only be delicate? Schematically, this argument is presented as ABC → E, where ABC is the set of non-aesthetic features and E is the aesthetic feature. We can imagine the vase with these features, but we can deny that it is delicate by seeing in the same object the features inappropriate to the concept of “delicate”. The vase can be pale pink, curved, slightly marbled, but too tall or too thin. It may be that a small clarified nuance such as the degree of a color, tonality, slight difference of a shape, movement or texture changes the aesthetic concept. One can see, for example, the grace and lightness in the dance of an obese woman or find a glaring pale painting. Furthermore, Sibley points out that many traits characteristically associated with one aesthetic term may also be similarly associated with other quite different aesthetic terms. In other words, the same combination of non-aesthetic features may be applicable to different aesthetic concepts. What is described, for example, as “delicate” can also be “tasteless”. Similarly, the non-aesthetic features of the term “screaming” can also be applied to the term “joyful”. However, the artistic technique that the artist uses to represent grace in his painting does not guarantee a positive result. It follows that non-aesthetic features do not logically justify or warrant the application of an aesthetic term.

There is no rule of application of the aesthetic concept since no description indisputably establishes the definition of the aesthetic concept. It may be impossible to give precise rules about how many relevant traits are required to form a sufficient set or in what combinations one or another trait is required. Basically, it is taste that teaches us how to apply aesthetic categories. Sibley points out that in exercising our judgment, we are guided by samples, namely a set of previous examples. Examples play a crucial role in inspiring us to apply aesthetic terms to new cases. However, one can always ask if this or the other aesthetic concept is really justified since no aesthetic term is applied mechanically.

The difficulty of applying an aesthetic term is compounded when it comes to the judgment of taste of contemporary art. Because of the use of different mediums and experimental techniques for the production of a work of art, the viewer is faced with a combination of non-aesthetic features that are incompatible with descriptions using certain aesthetic terms. For example, an abstract painting may be characterized by bright colors and curved lines: all are compatible with the aesthetic concepts “garish”, “flamboyant” or “fiery”. On the other hand, the dark spots and brown stripes on the black background can evoke the aesthetic concepts “discreet”, “harmonious”, “pale”. The same incompatible aesthetic concepts can be applied to Blue Poles painting by Pollock in which the color palette and paint trajectories make it difficult to interpret.

One can infer from these random spots that the painting is, or even could be, flamboyant or pale, chaotic or strict, happy or sad. The absence of a particular character in a work is a common problem in contemporary art. A painting or an installation may possess the kind of traits that one would associate, for example, with grace and elegance, but which fail to be graceful or elegant. Among contemporary works, there is an immense quantity of art objects that one is unable to describe in terms of aesthetic concepts. In His Infinite Wisdom by Damian Hirst, Tire test Column by Oscar Tuazon, *Y/Struc/Surf. by Marc Fornes, Dark Blue Panel by Ellsworth Kelly and many others fail to have any particular character whatsoever. Many features of these works of art are not much characteristic for particular aesthetic qualities. Moreover, conceptual art as waste, excrement, degraded objects or ready-mades even questions the notion of the aesthetic qualities of an object. It is debatable that we should make aesthetic judgements on a tangible object when it was not made by an artist himself. If we appreciate, for example, The Mona Lisa is on the stairs by Robert Filliou by its physical qualities, it is not a work of art that we judge, but rather an industrial object (21). It follows that many contemporary works of art do not allow us to make a judgement based on the characteristic features of the object.

In this respect, a classic work is easier to judge than a contemporary work thanks to the easily discernible non-aesthetic features. For example, in Van Gogh’s painting Irises that I was able to appreciate at the Musée d’Orsay in 2014, we can highlight the wavy curves of the irises, the intensity of the colors, as if Van Gogh was restoring the smells, the temperature and the presence of windy air. We can say that this painting is very precise, colorful and lively. Conversely, in front of the installation by Peter Buggenhout, exhibited at the Palais de Tokyo the same year, we are much more lost.

The structure, two meters high and five meters wide, appears at first glance to be a devastated building. To look for non-aesthetic features in this structure, on the one hand, chaotic, on the other, organized, would be a difficult task. This work only leaves the spectator to follow a labyrinthine course while being perplexed: should we appreciate this decor? Therefore, in contemporary art, there are far fewer non-aesthetic criteria that are essential for the application of aesthetic concepts. When we cannot identify the criteria to validate the use of aesthetic categories, we let the contemporary art market decide for us how to appreciate and classify the works. In this case, the economic value is a dominant criterion in the judgment of taste, because the price becomes the justification for our ignorance of the aesthetic concepts of a work of art.

By mentioning that the critic justifies or defends his or her judgments by non-aesthetic traits, Sibley wonders how one engages in aesthetic discussion. In other words, it is important to know how we lead others to see what they had not seen. In this regard, Sibley describes seven methods that we use as critics (22). First of all, the critic’s purpose is to mention or point out non-aesthetic features. One simply draws attention to features that can be easily discerned by the five senses. In addition, we can directly mention the character of a work by using aesthetic terms. Now, we often succeed in getting someone to see these aesthetic qualities by a chain of remarks concerning aesthetic and non-aesthetic features. We say, for example: “This is garish because the colors are brilliant” or “Note how the painting is expressive thanks to these sharp lines”. Sometimes we call attention to features by making use of similes, metaphors, contrasts or reminiscences: “See the pride in these lines, as if there were fire emitting a sharp flame”, “Don’t think you that these accidental stains have something of the chance of Bacon?”. In addition, repetition is used by drawing attention to the same lines and shapes. We repeat the same words, the same comparisons or metaphors. Finally, we use our intonations of voice, expression, nods, gestures and looks. When an epithet or metaphor fails, a critic does more with a wave of the arm or some other gesture. Consequently, the critic has recourse to a use of the keys that accompany his remarks. If we cannot prove by arguments, nor by sufficient conditions, that something, for example, is graceful, we can show our listeners what it is graceful. The basis for learning aesthetic terms is thus formed by our natural response to various non-aesthetic properties. In this sense, we are able to develop our judgment of taste by mastering the methods of discerning non-aesthetic qualities to touch the sensitivity and receptivity of our listeners.

One of the problems with Sibley’s theory has to do with the correct application of aesthetic terms. In a critical analysis, Ted Cohen argues that we are unable to distinguish between aesthetic and non-aesthetic terms. The classification of terms is not based on a clear and stable intuition (23). To defend his argument, Cohen shows that the reader is left perplexed by a long list of terms. Yet this argument can be answered by pointing out that verbiage or critical jargon depends on the language game that aesthetic experience shapes. In this case, taste is developed from learning how to say in each language game. In Sibley’s judgment of taste there is no room for intuition which discerns qualities spontaneously, since Sibley does not define taste as an innate faculty. We gradually master the more specific vocabulary of taste by focusing on the various natural non-aesthetic properties.

In another discussion, Joseph Margolis argues that aesthetic statements have no truth value, even if they rest on non-aesthetic qualities (24). His argument consists in discrediting non-aesthetic concepts by a form of non-cognitivism according to which one can distinguish between the fact of having and that of appearing to have. If sometimes one cannot be sure of what one sees in the object, one cannot however present them as reasons in support of aesthetic evaluations. From this point of view, Beardsley replies that the critic’s point is not based on the non-aesthetic qualities of the works of art which appear to be true or which are possible. Otherwise, criticism is meaningless because all judgments would be expressions of affect or emotion. If, for example, a certain quality in the picture seems red to me, it is unlikely that I will rely on it for an aesthetic statement.

Conclusion

We see today that the contemporary artist implements new techniques, works with new materials, changes the medium of creation, and therefore the place of exhibition. The artistic transformation during the 20th century resulted in an immense variety of aesthetic experiences devoid of coherence and organization. If in the age of the fine arts we could unify these experiences by an idea of the pure art of cultural hegemony, today we face a different interpretation of art and the absence of any hierarchy of appreciation. In this regard, contemporary art needs the principle or rule that would give meaning to notions of aesthetic experience. It is a question of rethinking the criteria of evaluation and even the judgment of taste to frame this aesthetic plurality in a conceptually organized way.

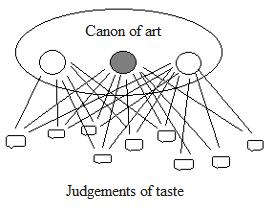

One of the possible forms of reaction to this immense diversity of objects and judgments consists in redefining the field of art on the basis of an artistic canon. Under canon, we mean the argument of authority which arises from the consensus of an environment or from the transcendental approach in the Kantian sense which predefine a domain of aesthetic experiences. One can, for example, give canonical status to the painted photographs of Teun Hocks and evaluate other works of art with reference to this canon.

However, this rather naive and neo-dogmatic strategy is not feasible in the era of postmodern pluralism where everyone expresses his or her preferences. It is hard to imagine how all diverse cultures accept the standard of judgment of taste from a particular work of art. Moreover, even if one could subordinate all artistic practices under the same scale of appreciation, this approach would mean the cancellation of the diversity of art objects in the name of a real domain of aesthetics. To put it in another way, artistic dogmatism can save us from the disarray of aesthetic experience, but necessarily through the abandonment of the majority of artistic practices that have no common link with the canon. A return to the old idealistic aesthetic theories is therefore impossible. We must try to form a new paradigm of aesthetics that responds to the organization of liberal culture with its diversity and relativity.

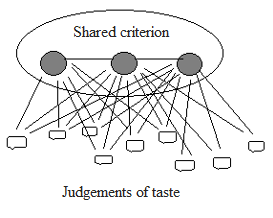

A second attitude that I adopt is to find similar and related elements in the diversity of artistic practices to escape the disorder of aesthetic experience.

Here, this position must agree with the universal character of aesthetic experience. It is not a question of the claim to universality but of the universality of judgment in the Humean sense which is assured anthropologically in all men. The unification of the works must therefore reflect the fact that every man has similar aesthetic experiences under certain conditions: the absence of prejudice, the versatile point of view, the mastery of the discernment of descriptive qualities in each artistic practice, etc. Hence this refinement of the judgment of taste which is provided by extensive experience and the learning of artistic grammar.

The proposed theory must take into account the fact that aesthetic judgments are susceptible to degrees on scales of appreciation. If we are going to be able to classify works of contemporary art according to specific traits or criteria, we can define the superiority of a work compared to others in the same classification. It follows that a relativity of the appreciations of the works depends on an intention of the spectator to judge a work according to one or the other criterion. These kinds of relativities are articulated and intertwine provided that the spectators join the same mode of apprehension.

References:

(1) The interview with Yves Michaud. Voir sur http://www.telerama.fr/scenes/yves-michaud-la-transgression-aujourd-hui-ne-va-pas-tres-loin-il-s-agit-d-une-audace-ritualisee-et-encadree,40623.php.

(2) E. KANT, Critique de la raison pure, op. cit., p. 54.

(3) See François LA ROCHEFOUCAULD, Maximes et Réflexions diverses, Flammarion, 1999

(4) By this argument, Lichtenstein wants to emphasize that aesthetic pleasure is not immediate and that the judgment of taste is based on a sum of aesthetic experiences.

(5) On this subject see Simone MANON, « Peut-on convaincre autrui de la beauté d’un objet ? », http://www.philolog.fr/peut-on-convaincre-autrui-de-la-beaute-dun-objet-kant.

(6) E. KANT. Critique de la faculté de juger, op. cit., §9.

(7) E. KANT. Critique de la faculté de juger, op. cit., p.63

(8) F. LA ROCHEFOUCAULD, Maximes et Réflexions diverses, op. cit., p. 162.

(9) HEGEL, Cours d’Esthétique, Introduction.

(10) Y. MICHAUD, La crise de l’art contemporain, op. cit., 236-237.

(11) P. BOURDIEU, La distinction. Critique sociale du jugement de goût.

(12) R. ROCHLITZ, Subversion et subvention, op. cit., p. 77.

(13) Ibid. p.138.

(14) F. LA ROCHEFOUCAULD, Maximes et Réflexions diverses, op. cit., p. 520.

(15) An irrationalism in art supposes that there are no more aesthetic criteria and everything is valid. A dogmatic rationalism, on the other hand, defines the field of art from an artistic canon. Under canon, it is about the argument of authority which arises from the consensus of an environment or from the transcendental approach in the Kantian sense which predefine a domain of aesthetic experiences. On this subject see Rainer ROCHLITZ, Subversion et Subvention. Art contemporain et Argumentation esthétique, p. 84-86.

(16) D. HUME, Essai sur l’art et le goût, op. cit., p. 75-124.

(17) Ibid. p.82.

(18) D. HUME, Essai sur l’art et le goût, op. cit., §16.

(19) Voir les oeuvres de Catherine Widgery sur http://www.widgery.com.

(20) Frank SIBLEY, « Les concepts esthétiques », op. cit., p.43-66.

(21) See the exhibition entitled « Collectior » (Le TriPostal de Lille) sur http://lauxiliaire.blogspot.fr/2011/11/collector-tri-postal-lille.html.

(22) Frank SIBLEY, « Les concepts esthétiques », op. cit., p.60-66.

(23) Monroe C. BEARDSLEY, « Quelques problèmes anciens dans de nouvelles perspectives » dans Esthétique Contemporaine, J-P. Cometti, p.50.

(24) Ibid. p.54.