Berkeley and Locke on Abstract Ideas

The main argument that Berkeley discloses in the introduction of a “Treatise” is that abstractionism is illusionary and inaccessible. In this context, Berkeley is criticizing Locke for his attempt to frame abstract notions that lead us to uncertainty and doubtfulness.

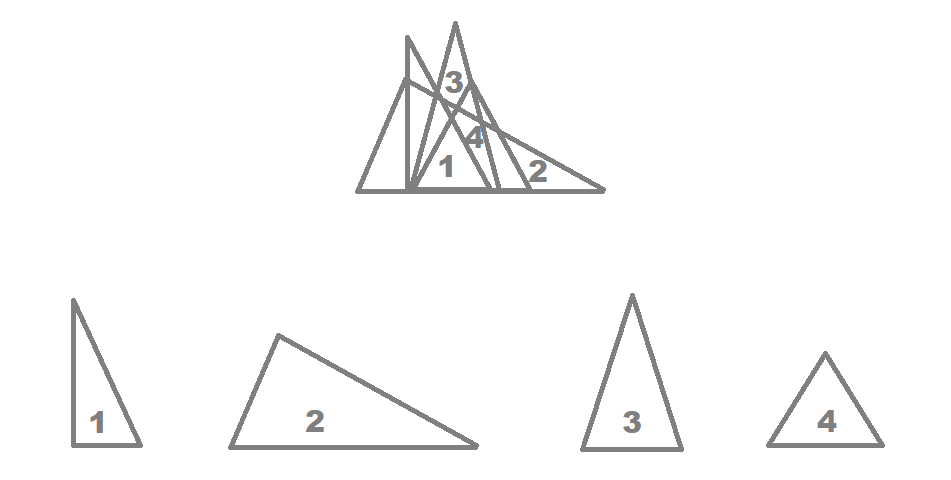

Locke introduces abstraction as one of the operations of mind, along with compounding, comparing, memory and naming. By abstraction, Locke means that mind is able to produce general ideas from particulars, leaving out the particular circumstances of time and place. The mind leaves out all peculiar things and retain what is common to all particulars. For example, to frame an abstract idea of a particular triangle, we should leave out all particular features of triangles and retain something that unites all of them. Thus, a most abstract idea of a triangle corresponds to all triangles, but does not coincide with any of them. This rule can be applied to ideas of one quality such as color, extension or to more compounded beings such as human, nature, animal, body. For Locke, abstract general ideas are of central importance since framing and retaining distinct ideas of all particular things is useless for language and beyond the power of human capacity.

Berkeley criticizes Locke for being one of those philosophers who depart from sense to reason to discover absurdities of our apprehension. Rationalists justify this skepticism by the imperfection of our mind, since our mind, being finite, tries to comprehend things that are infinite. Berkeley refutes this rationalistic claim blaming the wrong usage of faculties, namely ourselves, for causing uncertainties in understanding. So, Berkeley is proposing to make an inquiry concerning the principles that block up the way to knowledge.

For Berkeley, abstractionism is inconsistent with empiricism, for there is no way to derive such an abstract idea from our experience. For instance, we have an idea of a right triangle, oblique triangle, isosceles triangle and of a scalene triangle. In terms of Locke’s abstraction, idea of a triangle becomes general when it stands for all particular triangles. A word “triangle” becomes general when used for a sign of an abstract idea of a triangle.

For Berkeley, an idea of a triangle becomes general when it also stands for all particular triangles. However, Berkeley’s general idea is not the same as Locke’s abstract idea. Berkeley suggests that when we say “triangle”, we do not imagine an abstract idea of a triangle. Rather we consider any triangle, whether it is right, equilateral or oblique, that applies correctly to this general word. Berkeley believes that all ideas are images, so it becomes impossible to conceive of an abstract idea that could include both the ideas of a right and oblique triangle. Words become general by making the sign of several particular ideas and not of an abstract idea. Hence, universality belongs to particular things.

Though Berkeley retorts that abstraction is not necessary, it is questionable that we can consider concepts without having to form an abstract idea of them. For instance, when we say a general word “love”, do we really imagine a particular that stands for all variation of particular ideas of “love”? It seems that our mind makes a complete separation from particular circumstances that are connected to “love” and frames a completely separate idea of love. So, the Locke’s statement that we could frame an abstract idea seems to be plausible, even though it might be hard to explain how we do so.

Bibliography:

- Berkeley, George, A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge in Modern Philosophy, an anthology of primary sources, second edition, edited by Roger Ariew and Eric Watkins, Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. 2009

- Locke, John, Essay Concerning Human Understanding in Modern Philosophy, an anthology of primary sources, second edition, edited by Roger Ariew and Eric Watkins, Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. 2009