Research on nationality

In my paper, I will attempt to analyze national identity and lay it out as a concept that will be quite different from popular opinions. David Miller’s On Nationality (1) will be my theoretical framework, on which I will rely to develop critical questions and answers to them in the form of a monologue. The greatest challenge in outlining the idea of nationality concerns answering a number of questions: what constitutes a nation, how does one nation differ from another, and where does the boundary of a nation lie. The description and assessment of nationality in general is complicated by the fact that there are great differences between societies and diverse opinions about these differences. Even individuals of similar social backgrounds differ from each other, which may seem to call into question the project of national unification. Or is the idea of nationality purely mythical, a subjective notion that never existed and does not exist in reality? National loyalty has become something of a radicalized matter, easily manipulated in the political environment to support a particular political leader and party. An act of international aggression, appealing to the national idea and vital national interests, or discrimination of one social group over another within the same country – these are all examples of what critics push away from the national idea towards an international ideal or some form of cosmopolitanism. By rejecting the idea of nationality in favor of belonging to the human race, cosmopolitans think that the world will become more peaceful and orderly, but such an idea does not explain the differences between different national groups. In fact, there is something that embodies in us belonging to a particular group, and not to some abstract mass of people. We can suddenly feel something that connects us with a national brother. And even someone who is normally completely indifferent to nationality is likely to feel a sense of community when the fate of the nation is decided collectively. Miller emphasizes that even if we define a nation through the shared experience of a particular group of people living in a particular place, this is not enough to explain the weight of a person’s loyalty to their national identity (2). So, let’s try to understand the thesis of Miller’s description of the nation, avoiding as much as possible an abstract account of the concept of national identity.

Does a nation exist as a thing in itself or is it a purely subjective phenomenon? Miller is inclined to believe that nations cannot exist by themselves, unlike volcanoes or elephants (3). When we look at an elephant or a volcano, we can identify criteria by which we will understand that we are seeing this or that thing. With a nation, things are much more complicated. A nation, according to Miller, does not exist in the world independently of beliefs about itself. That is, if we ask a community what a nation is, we may get contradictory answers. A nation is like a team in which a set of people can see each other as part of an engine for achieving some common goal. Each member of such a cooperating team has collective obligations. A team can also be a bunch of people playing or working together, but their motivation is supported by personal ambitions, not team spirit. For Miller, it is futile to ask whether the Scots or the Quebecois constitute a distinct nation, since it is a question of interpreting what people believe about themselves. Moreover, no amount of empiricism that examines people’s beliefs about their place in the world will settle the question. The attitudes and beliefs that constitute a nation are very often hidden in the recesses of the mind, brought to full consciousness only by some dramatic event. In this respect, Miller takes an anti-realist position, according to which the definition of a nation rests not on logical reasoning but on the capacity of a person to believe that he or she belongs to a nation (4). One might even say that this corresponds to the pragmatic theory of truth: “A proposition is true if it is useful for our purpose.” So, it is up to us to decide whether the proposition “I belong to a nation” is useful, and therefore true. However, one might ask, is this statement really true? The fact that a statement is useful does not mean that it is true. It may be useful but false. Unlike Miller, I will still take a realist position, trying to argue that a nation exists regardless of what a person thinks about it. If we talk about a nation as a community, then we are, first of all, talking about something that everyone in this community shares. And this something exists regardless of whether we believe in our belonging to a nation or not.

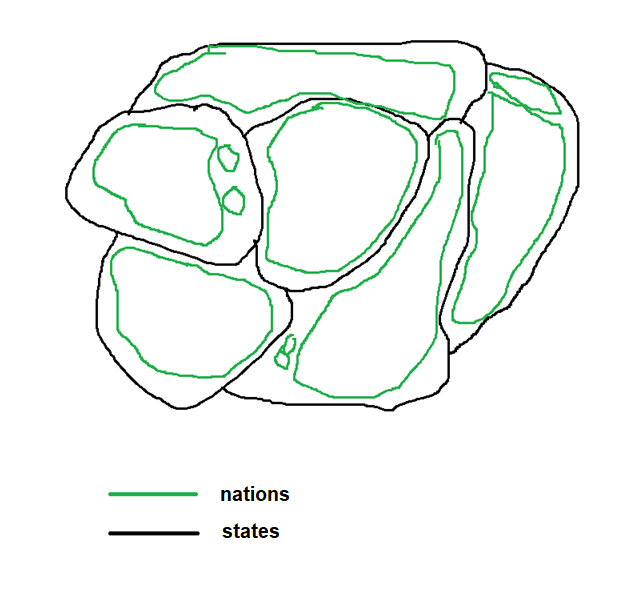

Miller notes that very often “nation” is used synonymously with “state,” which is a common misunderstanding (5). States can be multinational, as was the case in the Soviet Union, which had over a hundred nations. Nations can also be divided among several states, as in West and East Germany. Finally, nations can be dispersed as minorities in a number of states. The Kurds or the Palestinians will tell you. That is, the assumption that a nation is fully politically united in a single state completely distances us from the principle of the nation. Another false premise is to consider a nation as ethnically homogeneous. Let us say, somewhat conventionally, that an ethnic group is a community formed by a common biological origin (race) and cultural characteristics (language, culture, religion, etc.). Yes, a nation, like an ethnic group, can share common biological and cultural characteristics, but a single ethnicity is not a prerequisite for the existence of a nation. Many nations that had an exclusively ethnic character have, over time, encompassed many different ethnic groups. The most striking example is the American nation, which was originally ethnically Anglo-Saxon, but now includes Irish-Americans, Italian-Americans, and other ethnic groups. For Miller, ignoring the distinction between nation and ethnicity also leads the discussion of nationality to a false start (6). One can even cite the example of the so-called mono-ethnic states of France or Spain, which in fact did not historically consist of a single ethnicity. The Normans, Bretons, and Alsatians can be considered distinct ethnic groups in France, while the Basques and Catalans constitute a diverse “ethnicity” in Spain. Opponents of multinational states use the term “titular nation” that governs the state, and other ethnic groups do not have any influence on the country as a whole. But I would not dare to call a Norman or an Alsatian a national minority of France. Again, mixing the two phenomena of nation and ethnicity is an attempt to make the false assumption that a nation should be understood as an ethnically homogeneous community within its state. Such a position creates a repulsive effect of the elitism of the nation, when any sign of ethnicity makes a member of the community fall into the category of a non-titular minority. In such cases, the most simplified criteria for exclusion may be differences in biological traits, language accent, different thinking, or even differences in behavior. At the same time, supporters of monoethnic states themselves very often ignore the existence of ethnic differences inside the supposedly titular nation.

So, what does it mean to belong to a nation? Let us consider the five features that make up the idea of national identity and determine how rationally justified they are. Miller begins by analyzing the claim that nations are not aggregates of people distinguished by their physical or cultural features, but communities whose existence depends on mutual recognition (7). That is, defining national identity by such attributes as language or race is a false position. The example of Austrians and Germans shows that these communities may share physical and cultural features, but they still do not form a single nation, because they do not recognize themselves as a single whole. It is not so difficult to find examples of groups of people who mutually recognize themselves as a nation but do not share a common language or racial origin (Ghana, India, Belgium). So, when I identify myself as belonging to a certain nation, I mean that those whom I consider my fellow citizens share my beliefs. The problem with this attribute is that I can imagine myself as Chinese and be convinced that other Chinese will consider me one of their own, but this belief will not correspond to reality. If we assume that national identities are formed through the ideas of the members of the nation about themselves, then the term “nation” itself takes on a fluctuating effect, depending on the mood of the person convinced of his belonging. Today I believe in my belonging to the Albanian nation, tomorrow I will renounce it, but the day after tomorrow I will become Albanian again. With such a position, “nation” loses its objective meaning and moves into the channel of mythical beliefs.

The second feature of national identity according to Miller is historical heredity (8). Nations reach back into the past, losing their origins in the mists of time. In the course of national history, various significant events have occurred with the heroes of that time, and we can identify their actions as our own. Miller recalls Renan’s quote about historical tragedies being more important than historical glory (9). Sorrow is of greater value than victory, because it imposes duties and requires joint efforts. That is, a historical national community is a community of duty, because our ancestors worked and shed their blood to build and defend the nation. Those born into it inherit the obligation to continue the work of their ancestors, taking the nation forward into the future as well. The point is that a nation is not a group of people who practice mutual aid among themselves, which will disintegrate the moment such practices cease. Rather, the nation stretches back and forth across generations, and therefore cannot be abandoned by contemporary society. At the same time, Miller notes that this stretch in history is nothing more than an element of myth, which is largely based on the media (10). Nations are held together by beliefs, but these beliefs cannot be transmitted except through cultural artifacts: books, television, the Internet. In this context, nations are not entirely imaginary communities, meaning a false invention, but their existence depends on collective acts of imagination that find expression through such media (11). If we consider the formation of national identities in the nineteenth century, we can see that this process required the creation of a national language. For example, in Bohemia, only the peasants spoke Czech, while the nobility and middle class communicated in German. The emergence of a separate Czech nation required the transformation of Czech into a literary language. That is, the spoken dialect was transformed into a printed language by compiling grammars, dictionaries, and history of the language. And even the existence of Czech poetry in the Middle Ages was invented, a myth that played an important role in fostering the illusion that the Czech language and the Czech nation had deep historical roots (12). National history contains elements of myth because it interprets events in a certain way, and because it enhances the significance of some events and diminishes the significance of others. Miller again quotes Renan here, noting that the essence of a nation is to have much in common and to forget much (13). No Frenchman would recognize as his ancestors those who committed mass murder during the events of the Paris Commune. These events are not denied, but they are not part of the history that the nation tells itself. The reason for this veiling is that the formation of national units was largely the result of the contingency of political power, which satisfied territorial ambitions. Making one’s history false is an important factor in the formation of a nation, because no one wants to associate themselves with the artificial and forced nature of national genesis. As a result, fictional stories about the past of the people who inhabited a territory are now defined as national.

The third feature of national identity is that nations, as groups, act. They do things together, make decisions, achieve results, and so on (14). The nation becomes what it aspires to, even if these aspirations may lead to national shame. In this sense, Miller excludes the passive role of the nation, similar to how the church interprets the promptings of God. The problem here is that this exclusion imposes restrictions on the group member. Belonging to the Polish nation means actively embodying the national will. But if this will is only contemplated or passively interpreted, then the participant loses the very sign of national identity. That is, a Pole with a passive national position is not a Pole, because he does not participate in the unification of the past and future of the Polish nation.

The fourth aspect of national identity, Miller calls the geographical location of the nation. The nation encourages a person to constantly occupy the place that connects him with all the members of the group. In other words, the nation must have a home, a homeland. That is why the national community according to Miller must be political. If nations are groups that act, then these actions must strive to control a piece of land, in the sense of achieving or preserving statehood. This territorial element connects the nation with the state, which takes the form of legitimate power over this land (15). There is one point here. On the one hand, Miller excludes considering the nation and the state as one concept. That is, we accept the existence of nations within a multinational state. On the other hand, the national identity of a nation is built in the desire to achieve political control over the territory it occupies. As a result, an explosive situation of international separatism should arise, in which the exit of any nation from the state will always be ethically justified. This is not just about historically known nations that are seeking independence, such as Quebec, Catalonia, Scotland, but also about a multitude of multinational countries, including China, India, Russia, Belgium.

The final fifth element of national identity assumes that people of the same nation have something in common. This is a set of characteristics that Miller describes as national character, or a shared social culture (16). If we think of a nation, there must be some sense that people belong together because of shared characteristics. This may include political principles, such as a belief in democracy or the rule of law. This also includes social norms, such as filling out an honest tax return, giving up your seat on the bus for a disabled person, and so on. National identity can also encompass certain cultural ideals, such as religious beliefs or a commitment to preserving the purity of the national language. It follows that national identity cannot be based on a common biological origin, a view that leads us directly to racism. A common public culture is compatible with the membership of the community in a variety of ethnic groups. Even if every nation must have a home, this does not mean that every member must be born into it. Immigration should not create problems on the condition that immigrants share a common national identity, bringing their own distinctive ingredients. Miller gives the example of Americans and Australians, whose ancestors arrived in the New World with nothing but succeeded in the new society. Finally, a common public culture should not be monolithic and all-encompassing. It refers to some set of understandings of how people live together, not a set of characteristics that everyone must have equally. Instead of believing that there is a set of necessary and sufficient conditions for belonging to any nation, we should think of sufficiently distinctive features that constitute a unique whole. Miller emphasizes that national character must leave room for the flourishing of private cultures within a nation. That is, the food we eat, the way we dress, the things we listen to are not part of the public culture that defines nationality, because they are part of private choice. Taking these provisions of national character into account, its problematic features are outlined. Miller tries to encompass everything and nothing at once. By saying that national identity is formed by the distinctive features of each participant, which intersect in a strong network of shared culture, we miss the distinction of one nation over another. Imagine a hypothetical situation in which Brazilians and Irish unite in one state. Each of the members of the new community has something in common with each other: they pay taxes, vote in elections, support the same team. Despite the fact that the people from Ireland and Brazil are ethnically different peoples, speaking different languages, having different mentality and customs, they will constitute one nation. Miller’s national character becomes excessively general for any nation in the world.

So, we have five features of national identity, and each of them fails the test of rational justification. A deeper examination will reveal that a nation in the broadest sense is made up of people who differ both in mentality and in their customs and practices. Miller admits that if the canons of rationality are applied to the features of national identity, they turn out to be fraudulent (17). What are supposed to be the original features of a nation may be revealed as artificial inventions to serve political ends. But Miller tries to find a justification for national loyalty in ethical and political thought. He builds an argument according to which the myth of the nation performs a useful function in building and maintaining a national community. First, the myth determines that the nation has an extension in history that embodies a real continuity between generations. Second, the myth performs a moralizing role, showing us the virtues of our ancestors and encouraging us to live up to them. Strictly speaking, by accepting the idea of nations as ethical communities, we can accept the myth of the nation because it increases people’s sense of solidarity and duty to their fellow citizens. Miller uses a metaphor to reinforce the meaning of the myth of the nation (18). Imagine that the nation is like a lifeboat into which people have accidentally fallen. These passengers in the lifeboat must establish relationships with each other, that is, behave with dignity, work together to keep their activities afloat, etc. In the same way, people living under the same roof of institutions are obliged to respect and cooperate with each other, and it is not obvious why they should do so unless they think of themselves as bearers of a common history. It is the myth of the nation that appeals to their historical identity, to the sacrifice made in the past by one part of the community for the sake of others. The myth allows the nation to capitalize on the resources of the group when it needs them most. Therefore, members of a national community are subject to unconditional obligations by virtue of the fact that they were born and raised in that community. On the other hand, Miller speaks of the fluidity of national identities in terms of personal choices regarding compatibility or incompatibility with the values of the nation. Nationality is not chosen. It is acquired unreflectively, again, through the historicity of the national myth. But for a person who inherits a national identity, there is considerable scope for critical reflection. If someone is born Jewish and has no other choice but to become the bearer of some form of Jewish identity, he can decide what significance he will give to his Jewishness. Whether he makes nationality the central feature of his identity or only a secondary aspect. Furthermore, Miller emphasizes that, despite what nationalist doctrines claim, national identities are in practice not exclusive to bearers (19). For example, for Jewish Americans, national identity is linked to both Israel and America. They therefore maintain a dual loyalty, even though American immigrants take an oath of allegiance to the United States, requiring them to renounce allegiance to any foreign state. Miller’s mythic nation, however, is complicated by the fact that the continuity of national identity makes no sense for nations within a single state, because these nations are all in the same “lifeboat.” That is, for them there is one common historical stretch between the past and the future, and therefore one national identity. To say that the Sardinians should have a separate national myth to strengthen solidarity among the members of their community is like declaring the ineffectiveness of the Italian national myth in fulfilling its ethical and political function. If Miller attributes the meaning of myth only to states consisting of a single nation, then he reduces the concept of nation to the state. This is exactly what he tried to avoid in the beginning of his work.

In this case, I propose to recreate the idea of national identity on a different plane and investigate whether it is possible to substantiate it. In order to get out of the orbit of Miller’s concept of nationality, we will make a subtle shift in its meaning. Let’s start not from the question “Who am I?”, but “What do I know?”, as a member of a national community. We are talking about a certain set of practical knowledge and experiences related to customs, practices, means of communication, symbols and even implicit understandings with a neighbor or an ordinary citizen. Let’s call this combination the “code of the nation”. National identity is built on the fact that all members of the community know this code, and it does not matter whether they apply it in practice or not at a particular time. Then we can say that a nation exists because members of the community are able to feel and recognize the notes of the national character. Such a characterization of identity is to some extent close to any identity that is formed through the acquisition of knowledge and practices. Becoming a poet means being able to write verses, poems or other poetic works. In order to write poems, you need to have a set of knowledge and skills. Let’s consider them more closely. Firstly, you need to know the rhythm of the poem. They are two-syllable (chore and iambic) and three-syllable (dactyl, amphibrach and anapest). Secondly, it is important to know how to use various artistic means, such as metaphor, metonymy, hyperbole, allegory, comparison. Thirdly, it will be very difficult to write without reading poems by other poets. Therefore, you need to read a lot of both classics and the work of modern authors to know about different styles and forms of poems. Reading in general will increase the general literacy of using the language in which the poem will be written and expand your vocabulary. Fourthly, without feeling, poems will not be able to attract anyone’s attention. You need to write what you feel at the moment, then the poems will become more accurate, the words – brighter. Fifthly, you also need the skill of imagination, figurative and associative thinking to create unexpected and catchy images. As we can see, the formation of a poet goes through the study of the rules and actions that give value to poetic works. Similarly, nationality is acquired by a person through the initiation and entry into a local language game according to the type of Wittgensteinian concept (20). The main idea is that language is used in context and cannot be understood outside this context. Wittgenstein gives the example of “Water!”, which can be used as an exclamation, an order, a request, or an answer to a question. The meaning of a word depends on the language-game in which it is used. At the level of a nation, a language game refers to any actions that acquire meaning only if we perform them in a context shared by other members of the group. A member of a national community must study the meaning of the actions of his fellow citizens by applying the common rules of the game in practice. That is, to become a Quebecer, one must immerse oneself in the Quebec way of life in order to gain the opportunity to create according to its rules, to create with the Quebec code. Of course, this takes time and inspiration, but in most cases the code of the nation is learned without even thinking from the time a child is born, just as one learns to speak or walk. If it is a Quebec immigrant, then he also has every chance of becoming a Quebecer through studies, work, family, friends, etc., in the same environment in which other Quebecers operate. When he is able to navigate the Quebec language game and act according to the rules of this game, he will acquire a Quebecer identity. Only in this way does national identity become not a mythical entity, fluctuating from the idea of the members of the nation about themselves, but an existing thing with its own criteria of definition. Then when we say about a group of people that they constitute a nation, we are not talking about their self-esteem, physical characteristics or behavior, we are talking about the set of knowledge and skills that they share and which constitutes the code of the nation. Groups that form as nations do not have any particular geographical segregation. It can be as a village, a city, a region, or a combination of each of these. At the same time, several nations can coexist side by side, intersecting with each other as language games.

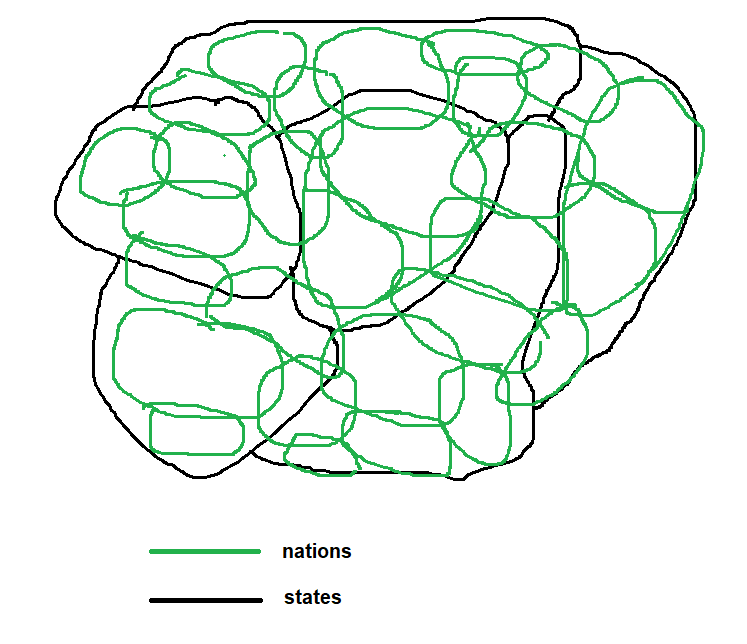

Let us trace further the national identity and try to find out where the boundary of the nation lies. If we build a nation on the basis of the Wittgenstein’s concept of a language game, then let us try to separate from it the theoretical basis for the concept of a boundary. For Wittgenstein, in general, setting the boundary of a game makes no sense in the classical sense (21). He gives the example of the concept of “number”, emphasizing that we can give it hard boundaries, that is, use the word “number” for a very limited case. But we can also use the concept of “number” in such a way that the spread of its concept has no limits. This is how we use the game. We can define the boundaries of a game only for some special purpose, but this does not make the concept more usable. Then Wittgenstein asks the question of how to explain to someone what a “game” is. If the concept of “game” has no boundaries, then what, in fact, do we mean by “game”? If we compare the concept of a game to a region and say that a region without clear boundaries cannot be called a region at all, then this probably means that such a concept is meaningless. But Wittgenstein gives the example of him standing with someone in a town square and saying, “Stand here!” He does not bother to draw any boundaries, but simply makes a pointing gesture, as if pointing to a certain place. And this is how we can explain what a game is. We give examples and intend them to be perceived in a certain way. If we ask where the border of the Basque nation is, we will encounter a similar answer. We cannot simply determine where the nation still counts and where it no longer counts. But we can start playing the Basque code and expect a reciprocal reaction to our game. If the response to our message does not make sense, then we exclude this response from the scope of the nation code, and thereby draw its border. That is, the nation, as a concept, has no boundaries, unless we begin to exclude meaningless combinations from distribution, playing by the rules of the language game. And yet, the removal of combinations from the sphere of the game is also part of the game. When we draw the boundary of the nation, this does not yet mean what we are drawing it for. It may be for players to jump over it, or it may show where the property of one person ends and another begins. It follows that the internal quality of the nation is that it overlaps and crisscrosses with other nations, creating a network of language games. This is how the activities of the poet and the writer intersect according to similar rules. The poet creates works of poetic genres, such as verses, poems, dramas in verse, while the writer focuses on prose. But both use similar skills and practices to write their works: reading the works of other authors, the skill of imagination, figurative and associative thinking, the use of various artistic means, etc. In this field of intersection and overlapping similarities of language games of nations, the border of a state, region or even a city makes no sense. In Montreal, this network of nations represented by the French, Italians, Irish, English, Haitians, Scots, Chinese, indigenous peoples of Canada, Quebecers and so on is clearly felt. Each of these national groups can orient themselves in two or more language games. At the same time, any established language game on the territory of Canada is considered by the state as Canadian. That is, Canadian nationality does not actually represent a separate language game, but is rather an aggregate of intersecting nations of Canada. This also applies to the so-called “mononational” states. A native inhabitant of Maastricht in the Dutch province of Limburg plays by the rules of a code that is more similar to the code of the Flemish in Belgium. At the same time, this Flemish nationality of the Maastricht inhabitant is combined into a Dutch nationality, which brings together all nationalities within the borders of the Netherlands. In a monoethnic corner of Ukraine, two cities – the capital Kyiv and Malyn, which are 100 kilometers from the capital – have communities of different national identities, since each of them significantly differs in the rules of the game regarding the use of the code of a particular Ukrainian nation. There are many such examples. It turns out that the very concept of a nation state does not make sense, because within the borders of any state we will have an intersection of language games that will go beyond the borders of the state territory. If in the central regions of Slovenia, we should expect a homogeneous code of the nation, in the remote corners of the country on the borders with neighboring states the use of other language games will take place, thus forming other Slovenian nations. It would seem that dwarf nations such as Monaco or the Vatican should constitute nation-states, but they will not be exceptional. The language game of these states will be similar to one of the language games of the French or Italian nations. That is, in this case it is not the state that unites nations, but the nation that unites states. And even the Republic of Nauru will not be an exception. This dwarf state on the coral island of the same name in the western Pacific Ocean is located far from other states, but was inhabited by the indigenous peoples of Micronesia and Polynesia. Therefore, the nation code for Nauru is very likely to be similar to that of one of the nearby island nations, such as Kiribati or Tuvalu. Thus, if we were to conceptually map nations on a world map, they would look like this in modern usage.

As a rule, the nation is identified with the concept of the state. In some cases, the concept of the titular nation is used to separate any national diversity along ethnic lines into a separate small group next to each other. In the following scheme, we have a map of nations according to the diversity of the code, where we will see a complex intersection of nations in a network of language games and which does not depend on the state border, culture, language, or biological origin of people.

That is, according to this scheme, the modern use of the concept of nation loses its meaning, because it does not reflect the essence of the national identities of countries. The nationality of a country becomes an aggregation of national identities of communities within the state or is part of an interstate nationality. If, for example, we talk about French nationality, then we, first of all, mean the unification of all identities of French nations into one formal concept. This includes the language games of Parisians, Marseillesians, Lyons, Guadeloupians, Alsatians, Basques, Corsicans, Normans, Bretons, Catalans, Gascons, Vendeans, Algerians, Benins, Senegalese and many others. And each of these French people owns at least the rules of two or three codes of nations. However, such a collection of national identities will not have any exceptional features why certain nations and not others fell into this French nationality. It follows that nationality of France is a purely technical concept created by the state on a territorial basis. And this applies to any nationality equated with the state.

Miller’s next claim about national identity is that nations are ethical communities (22). Recognizing national identity, Miller argues that we should have special responsibilities to our fellow citizens. These are the same responsibilities that we have to our family, our school, our local community. That is, if I belong to a certain community, I feel a sense of loyalty to that group, and this is expressed in the fact that I pay special attention to the interests of the members of the group. Miller gives the example of two students coming to him for advice. His time is limited and so he gives preference to the student who belongs to his college. For Miller, these responsibilities are reciprocal, in the sense that he expects other members to give special weight to his interests just as he gives special weight to theirs. However, the ethical obligations of nationality differ from those of other communities in two main respects. The potency of nationality as a source of personal identity means that its obligations are felt very strongly and can extend very far – people are prepared to sacrifice themselves for their country in ways they are not prepared to sacrifice themselves for other groups and associations. But at the same time, these obligations are uncertain, because they are the subject of the political mainstream, or they flow from the public culture. In other words, the public culture establishes an idea of the character of the nation, fixing its obligations. And these, in turn, are the product of political debates and ideological coloring. For example, some national cultures may attach importance to individual self-sufficiency. Others will place greater emphasis on collective goods and will believe that compatriots have obligations to participate in various forms of national service. Here again Miller operates on the assumption that the borders of the nation coincide with the borders of the state. Yes, citizens of any state have rights and obligations that arise simply from their participation in practices from which they benefit, due to the principle of reciprocity. As citizens, they enjoy the rights to personal protection, medical care, free school education, etc., and in return they are obliged to obey the law, pay taxes, and generally support a system of cooperation. However, these rights and obligations have no ethical content, because they are part of the language games of nations. If a Bulgarian plays in the language game of one of the Bulgarian nations, he must follow the rules of use of this game in practice. This may entail his obligations to pay local taxes, give up his seat on the bus to an elderly person, tie a martenitsa (a twisted white and red woolen thread) on his arm on the occasion of the celebration of Baba Marta, etc. But if he withdraws from participation in the language game of the nation, he will depart from the rules of use that establish his rights and obligations as a participant. At the same time, he will remain a bearer of national identity, because he will retain the knowledge and skills of participation in the language game of his community. Similarly, a poet who writes a poem follows certain rules that impose obligations on him regarding the formation of rhyme, taking into account metrics and structure. Does he have an ethical obligation to follow the rules of writing a poem? No, he doesn’t. The extent to which he follows the rules speaks only about the degree of his participation in the language game of poets. Finally, Miller’s remark that the ethics of a nation are formed by social culture and political processes only shows how conditional and changeable this ethics is. Any person can interpret his belonging to a nation differently and from this draw certain conclusions about his duties to his compatriots. In addition, social culture and the duties of nationality that arise from it can change over time as political institutions, the general level of education, etc. develop. That is, Miller’s ethic of nation turns out to be an artificial invention, based not on tradition, but on social processes of interaction. It is primarily a tool for regulating relations between members to ensure the stability of the state system. Therefore, Miller emphasizes that there are good ethical reasons for the borders of nationality and the borders of the state to coincide (23). In this case, if someone asks himself why he pays taxes, he will find two answers for himself. The first concerns his duty as a member of the nation to support social projects and to meet the needs of other compatriots. The second answer will emphasize his duty as a citizen to support institutions from which he expects, in turn, benefits. Together, these answers provide a strong stimulating effect of contribution, which would be difficult to achieve solely on the basis of reciprocity between members. Specifically, Miller uses the concept of ethic of nation to ensure more effective governance of the state. At the same time, if the strengthening of statehood depends on the degree of coincidence of the border of the nation with the border of the state, then multinational states turn out to be vulnerable and ineffective by their very nature. In the case of presenting any state as a territory of intersection of language games of nations, we must redraw the entire world with new state formations in order to achieve the coincidence of the borders of the nation and the state and ensure the stability of state cooperation.

Let us consider in more detail Miller’s next claim that national communities have the right to political self-determination (24). He admits that in some cases nations are so geographically mixed with other groups that this aspiration may be futile. However, Miller gives a number of reasons why it is important that the boundaries of political units coincide with national boundaries. First, he suggests that a nation whose borders do not coincide with its political ones will find it very difficult to achieve a regime of general justice. He gives the example of the economically prosperous Slovenes during the Yugoslav federation who were not very satisfied with the distribution of resources and the subsidization of investments in Serbia or Montenegro (25). General justice for Slovenia was not observed because the Slovene nation had a right to the resources created by its members but felt that it was losing more in relation to other communities. If Miller takes into account GDP per capita to determine the fair distribution of a nation’s resources, then national self-determination is not always economically justified. Yes, the Catalans, who are almost catching up with the Madridites in terms of GDP per capita, might feel more justice if they left Spain. But the same cannot be said about Quebecers. In terms of the ratio of the province’s gross domestic product to its average annual population, Quebec is not at the top of the list compared to other provinces (26). It turns out that the least productive nations in a multinational state have no point in seeking political self-determination, because their achievement of general justice is in doubt. Moreover, we cannot even be sure that Catalonia would remain as economically productive after gaining hypothetical independence from Spain. It is impossible to calculate all the factors of the cause-and-effect chain that permeates the Catalan economy in the system of economic relations with other regions of Spain and countries of the world. Therefore, if Miller links the desire for a political definition of the nation with the achievement of the pinnacle of social and economic justice among its members, the result of such a desire may be futile and lead to the opposite.

Another meaning of national self-determination, Miller puts the protection of national culture (27). That is, national culture needs protection from the state. The point is not that public culture cannot exist without state regulation, but that it would be unwise to entrust it to private individuals. Miller gives the example of the owner of a television station who sincerely wants to make high-quality dramas and investigative documentaries, but in a competitive market he may have to buy cheap imported soap operas in order to survive. Thus, the only way to prevent the decline of national culture is to use the power of the state to protect aspects that are considered important. And here the question arises. Where is the guarantee that the state, whose borders now coincide with the nation, will create better conditions for the existence of national culture? Let us imagine that a multinational state breaks up into small nation-states. Now each of them has full control over its public culture, but must withstand even greater influence on it from now on from neighboring states. And it is good if the newly created state is financially self-sufficient, but in the modern world of international economic relations, even a wealthy state community must adapt its national culture to the challenges of external factors. It is not always that a supposedly mono-national state will care in the interests of preserving and spreading its national culture to the detriment of economic interests. For example, the Netherlands, which is historically a rich trading state, has grown a separate national layer of expats working on a permanent basis in local enterprises (28). These are people who are well integrated into the Dutch system of life and cooperation, while not speaking Dutch at all or using it very basically. We are not even talking about a means of communication, but about a different code of the nation. Dutch expatriates have created their own national culture, which exists in parallel with the original Dutch one, and which the Netherlands also recognizes as Dutch, granting its speakers Dutch citizenship. But the worst result of protecting public culture can be expected by a mono-national state that will find itself in a very poor financial situation and will depend on international subsidies from outside. One can cite the example of Nauru, already mentioned above, whose economy has historically been based on the extraction of Nauruite (29). When primary phosphate reserves were exhausted by the end of the 2010s, Nauru sought to diversify its sources of income. In 2020, Nauru’s main income came from the sale of fishing rights in territorial waters and from the Australian immigration detention center. That is, the country is significantly dependent on foreign aid from other countries, in particular from Australia and New Zealand. Although Nauru’s state borders coincide with those of the nation, the country has little chance of preserving and spreading its nation code, unless, of course, it existed and has already merged with that of one of the nearby island states of Micronesia and Polynesia. Miller insists on a homogeneous state, recalling cases where in a multinational state the dominant group had a strong incentive to use state power to impose its own culture on weaker groups (30). He cites historical examples of attempts to forcibly assimilate national minorities into the culture of the majority, ranging from the forced Magyarization of ethnic minorities in nineteenth-century Hungary to the consistent policy of the Turkish state to destroy the cultural identity of its Kurdish minority. To begin with, titular nations tend to ascribe to themselves a greater degree of cultural homogeneity than their members actually demonstrate. It is meant that any majority nation actually consists of several cultural identities and which are very difficult to impose on another nation, because they do not represent a complete code to replace. The assimilation of a national minority by forced learning of the language of the so-called titular nation will in no way change the minority’s ability to create according to the code of its community. And how can one replace one national code with another? A community can acquire knowledge and skills of another national code, but in no way refuse to use the code that it knows best, and in the best-case scenario will use both. Similarly, a poet who knows best how to write poetry will not lose his skill just because he learns to write prose. That is, the acquisition of other codes of nations is inherent in national identity, just as the acquisition of knowledge and skills is inherent in any person. Only by forced eviction or physical destruction of a community can one replace one national code with another in a certain territory. To some extent, Miller’s position on the desire to turn every state into a mono-national one is understandable, since history has many tragic cases of people’s resettlement associated with multinational states. For example, the Slovenian Maribor, Ptuj and Celje had a German-speaking majority, and the Ukrainian Lviv had a Polish-speaking majority before the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (31). But again, according to the theory of language games of national communities, the reformatting of nations can only occur in a multinational state and ultimately lead to the formation of a new multinational state, because mono-national states in a permanent pure form do not exist. Even if we assume that Palestine can embody the image of a mono-national state (albeit with a significant part of the community residing in many other countries), its political self-determination in no way strengthens Miller’s argument that the best conditions for preserving the common culture of a nation can be created only if it coincides with state borders. Let us imagine that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is resolved in peace and prosperity for both states. Then it can be assumed that Palestine will return to its homeland its members wandering around the world, thereby increasing the diversity of Palestinian nation codes, as Israel did at that time. That is, Palestine is being created from the bowels of multinational states and, ultimately, its national self-determination can only lead to the creation of a multinational Palestinian state. Thus, according to Miller, there are strong empirical reasons to believe that national cultures will be protected most effectively when they are nurtured by their own states, and at the same time, these empirical reasons can be contrasted with others in which the political self-determination of a nation leads to the formation of various language games that cross the primary one. Whether the original common culture will benefit or decline from the neighborhood with the newly created depends on many difficult-to-predict factors, such as the political system, economic development, geographical location of borders, relations with other countries, etc. But in one case or another, Miller’s reasoning about the harmony of state government within the nation loses its meaning, because it does not correspond to the nature of the development of a nation in its neighborhood with others.

Finally, Miller notes that we should consider national self-determination as an expression of collective autonomy (32). This claim is based on the assumption that people have an interest in creating a world together with others with whom they identify. Even if this desire can be realized in different forms, such as enterprises, associations, the state is still able to best express the will of collective autonomy. But for this to happen, it is not enough for the state to coincide with the nation. The state must be democratic in form to guarantee the will of the people. That is, according to Miller, a democratic state can guarantee that national self-determination is truly national, since in such a state people have a greater sense of control over their destiny. But even assuming that we seek to build something together with someone with whom we have something in common, why should we necessarily do so in a political formation? The will of collective autonomy is best fulfilled in an environment in which decisions are made by the smallest possible number of players without intermediaries. In other words, the more local the aspect of decision-making at the level of ordering and execution, the more likely it is that what has been ordered will be carried out with full control of the entire process. It is better to be in a group of two decision-makers than two hundred, then the command will be clear and certain. In the same way, it is better to have two executors than two hundred, so that the will is carried out clearly and without misunderstanding. In this regard, decision-making in the political dimension can in no way be the best for expressing the will of the nation. A state formation involves so many unknown factors over which the players have no influence that a nation under such conditions is more likely to play roulette than to resolutely carry out the common will. And it does not matter what form the state formation takes. If in an authoritarian state there is no illusion that the will of the nation is in the hands of a few individuals, then in a democratic state there is a simple illusion that the nation has a will and that it influences something in the collective desire to move in the desired direction. This is not to say that the nation must choose an anarchic form of government, which Miller mentions in the example of the German anarchist Gustav Landauer (33). Rather, it is meant that the will of the nation is as illusory as the will of poets. In what way is it expressed if not in the different interpretations of individual members of the national community? Moreover, these interpretations can be completely opposite. The nation has no obligation to fulfill its will, because it is impossible to determine the common movement of something that moves in different directions. So, by saying that the goal of political self-determination is built into the very idea of the nation, we distance the term nationality from the aspects that rationally follow from it.

Miller further attempts to strengthen the concept of the mono-national state by changing the direction of the argument. He suggests asking why states or the political power of states are likely to function most effectively when they encompass only one national community (34). It’s that much of the state’s work involves achieving goals that cannot be achieved without the voluntary cooperation of its citizens. For this work to be successful, citizens must trust the state, and they must trust each other to do what the state requires of them. Shared identity carries with it shared loyalty, and this increases the confidence that others will be held to a reciprocal obligation to cooperate. This key claim underlies Miller’s argument that cultural homogeneity generates solidarity among members of a nation. But it is not difficult to counter that solidarity can also arise between individuals with very different national identities. In general, nationality cannot have any bearing on whether or not we trust a person. This is the assumption that nationality forms the same opinion about each other in people with a common national identity. Yet what moral qualities can we assume from someone we consider a national brother? They can be both positive and negative for us, which depends more on completely different aspects of the personality than on national ones. A poet can be both an enemy and a friend to a poet, because the language game does not program the participant’s attitude to the environment. Similarly, the code of a nation only gives meaning to the activity of each of the participants in the game, without generating a compatriot’s judgment about a particular language game. Belonging to a nation does not create sympathy or antipathy towards another nation. If we build national identity on the attitude towards something, then the nation completely loses its essence, because then it will depend on the emotional mood. In this case, one cannot do without a state machine. It is on the relationship to other states and their opposition in the form of nations that the collective nationality of states is built, which has no fundamental unifying factor, except for the state border. Only in this way does the state try to ensure within its borders the fragile construction of various national communities, since the emotions and attitude of each member of the nation to non-state objects are easy to manipulate. In this sense, the emotional projection onto the outside world is not an integral part of national identity and in no way affects the nation itself, but the state uses this plane to create its so-called state nationality. For example, one of the unifying factors of all Indian nations is hostility to Pakistan, since on this emotional background the state builds a unifying state national identity. Similarly, Pakistani nations are guided by the auspices of hostility to India, creating a technical Pakistani nationality. To be Indian, then, is to dislike all Pakistanis, and conversely, to be Pakistani is to despise all Indians. Miller provides several examples of countries that supposedly demonstrate the effectiveness of cultural homogeneity for governance (35). Democracies such as Switzerland and Canada, which have successfully implemented policies aimed at social justice, have a unifying identity. Miller acknowledges that these countries can be considered multinational to some extent, but they still demonstrate the unifying force of solidarity that results from a single national character. In Switzerland, national identity in the nineteenth century was quite consciously forged by myths of the origin and resurrection of national heroes, despite separate linguistic, religious, and cantonal identities. Miller also cites Switzerland’s decentralized government and the development of democratic institutions as contributing to the formation of Switzerland’s national character. As for Canada, it also boasts effective government and social justice. Despite the fact that French-speakers and English-speakers consider themselves different types of Canadians, they have a common Canadian identity. Here Miller points to a source of Canadian pride, such as national health care, which distinguishes Canada from its American neighbor. That is, in Canada there are institutions that have become a unifying component of the identity of the Canadian nation. For a comparison with Switzerland and Canada, Miller gives the example of Nigeria, which is an organization of several ethnic groups. The politics of this country takes the form of a struggle between these groups for dominance in the form of bargaining and bribery. And this is because in Nigeria there is no mutual trust between national groups, and therefore there is no common national identity. As for Nigeria, I will not deny that it is a multinational country, although this fact in no way justifies the consequences of the Nigerian political power. As for Canada and Switzerland, I will argue that these two countries are also multinational. The problem here is that Miller repeatedly replaces the concept of nation, which exists as a language game of the community, with a nation that exists only in the imagination of state institutions, that is, a mythical formation of the state. Yes, Swiss watches, Swiss chocolate, Swiss banks, Swiss cheese, the Swiss electoral system of cantons – these are all unifying ideas around a single Swiss nation. But we are talking about a technical nation that does not exist in reality. Similarly, one can pick up a combination of general definitions about any country, often as clichés, that will indicate the existence of a so-called single national identity in it. But how can one deny the use in Switzerland of completely different codes of activity of the same French-speaking, German-speaking, Italian-speaking and Romansh-speaking nations? The same applies to Canada. The inhabitants of Vancouver, Toronto and Montreal differ not only in different linguistic, ethnic and social differences, but also in completely different ways of life. And when Miller mentions the Canadian health care system as a unifying factor of the nation, he forgets about the equally significant differences within this system between Canadian provinces. Very often this concerns the waiting time for a narrow specialist and finding a family doctor, which in some provinces can be a long and difficult process (Quebec), and in others, on the contrary, simple and convenient (British Columbia).

After arguing for national self-determination, Miller responds to criticisms that the principle is not applicable to the real world (36). To avoid political chaos, he suggests defining a number of practical conditions that must be met before a sub-community can legitimately claim to establish its own state. One condition is set by default. A group that wants to become politically independent must have a national identity that is distinct from the nationalities of the other members of the state. Next, we must be sure that the territory of the group does not contain a minority whose own identity would be radically incompatible with the identity of the group. Otherwise, instead of creating a viable nation-state, the secession of the group would simply recreate a multinational order in a smaller state. Some attention should also be paid to the members of the group who will remain in the parent state rather than in the newly created state. The effect of secession should not leave them in a weak position. Miller mentions Quebec’s desire for independence, arguing that this argument is against the separation of the Quebec nation (37). If Quebec were to secede from Canada, it would destroy the dual identity that Canada had sought to achieve and would leave French-speaking communities in other provinces isolated and politically helpless. Another condition concerns the viability of the newly created state in the sense that it must be able to defend itself territorially. But at the same time, it must not weaken the parent state by making it extremely difficult to defend it militarily. Finally, the territory being seceded must not contain the entire supply of some important natural resource of the state. Here Miller points out that the separation of Scotland would be impractical because the prospect of extracting significant amounts of oil from what would become Scottish territorial waters would violate this condition. The problem, however, is that Miller makes any secession of a group from a state unjustifiable. A community seeking state independence will in any case have other national groups on its territory, or will leave its members unprotected outside the newly created state. Not to mention that this act of secession will weaken the state, which loses territory or resources, and the group, which will be unable to guarantee economic viability or be unable to defend its borders. And when Miller points out the appropriateness of autonomy or the extension of regional rights within states for the Catalans, the Scots, the Quebecois, the indigenous peoples of the United States, or the Saami in Sweden, he surprisingly approves of the partition of Bosnia into independent states during the Bosnian war (38). His argument is that before the outbreak of the military conflict that occurred in Bosnia and Herzegovina between 1992 and 1995, the nations were evenly mixed throughout the geographical area. Therefore, partial autonomy over the territory could not be the answer to the conflict. The only possible solution was a form of power-sharing between the groups, guaranteeing each one at least a certain measure of self-determination. Miller, however, overlooks the fact that the end of the conflict resulted in the creation of a multi-ethnic Bosnia and Herzegovina, where Bosniaks (50%), Serbs (30%) and Croats (15%) currently live. This is precisely the fact that should condemn Bosnia and Herzegovina’s secession from Yugoslavia under Miller’s principle of national self-determination, not to mention the fragile capacity of the newly created country to defend its borders and its military dependence on other states. Miller first speaks of the internal desire of each nation for its territorial borders to coincide with the state’s ones, and then sharply backtracks, providing conditions that make this desire impossible.

In the next part of his work, Miller explores the internal effects of state nationality on a national minority, or rather, ethnic identity, the essence of which may contradict the state policy of uniting the nation within the country (39). In this regard, Miller draws attention to conservative nationalism and radical multiculturalism as the two most contrasting forces of the political vector of the state in the 20th century. Conservative nationalism is based on the assertion that national identity is something that is given to us by the past, by our ancestors, and therefore we must protect it from external forces that weaken it. Having the greatest meaning for us, this collective identity must be passed on to future generations. It follows from this that we should decide such issues as the education of children or immigration not by the assumed rights and freedoms of a person, but by the need to preserve a common national identity. In contrast to nationalism, radical multiculturalism or liberalism sees the state as an arena in which many kinds of individual and group identities should be allowed to coexist and flourish. The state should not simply tolerate, but equally recognize each of these identities. National identity then inherently loses its value, because it is seen as a product of political manipulation. At the same time, identities derived from gender, ethnicity, religious beliefs, etc., should be celebrated as authentic expressions of individual differences. Miller clarifies that neither position is adequate when examined in more detail. Conservative nationalism supports the idea that national identity implies loyalty to authority. The nation is compared to a family, a community that has built into itself an unequal relationship between the parent-state and the child-members. The family demands from its younger members not only loyalty to authority but also piety, and this, in the conservative view, constitutes the proper patriot (40). Without this piety, a person cannot properly perceive himself as part of a historical national community, and therefore degrades. Along with this degradation, moral orientation is lost. But nationalism suffers from serious consequences of its doctrine. First, since the state draws its power partly from the power of the nation, it must give formal recognition to the institutions through which state power is expressed. This immediately contradicts the idea that the state should be neutral towards many different cultural practices, such as religious ones. The state should not grant the religious institutions of ethnic minorities the same status as the national church, since this would mean weakening the authority of national institutions. Second, a conservative understanding of nationality assumes that the beliefs and practices that constitute it need to be protected from the caustic acids of criticism (41). Through myths, state institutions enter the lives of citizens and absorb them. It is therefore a legitimate task of the state to ensure the preservation of national myths. If this conflicts with liberal commitments such as freedom of thought and expression, then such commitments must be abolished. Sanctity, intolerance, alienation, and a sense that the meaning of life depends on obedience as well as on vigilance for the enemy are all real prices that a community must pay for the political consequences of conservative nationalism. Third, a conservative conception of nationality will inevitably lead to a discouraging, if not prohibitive, attitude towards potential immigrants who do not yet share the national culture. Conservative opposition to immigration is sometimes reduced to mere racism, as nationalists see the influx of people who have no respect for national institutions and practices as destabilizing. Here Miller cites Casey’s rhetoric about the Indian community in Britain, which is antipathetic to British nationalism. Casey proposes the voluntary repatriation of a significant part of these communities as the only possible way to preserve the British nation (42). The problem with this position, as Miller notes, is that nationalists are well aware of the constant evolution of national identity, and that the traditions they wish to uphold may be recent inventions. Yet while they may call for piety and respect for these traditions, they may not share them. Moreover, nationalists find it very difficult to rely on the authority of state institutions in the absence of universally respected national symbols. But I would call the problem of nationalism the fact that, paradoxically as it may sound, it does not represent any of the nations of the state. The nation of a nationalist is a mythical community with a certain set of beliefs and traditions that have no relation to the values of the actually existing community within the country. And therein lies the difficult fate of nationalism. It tries to artificially unite all language games on the territory of the state into one, taking from some something that, in its opinion, is weighty and comprehensive. But such a newly created game is doomed in its infancy, since the application of its new rules in practice loses a certain meaning for the community. It is the same as taking some rules for writing a poetic work, and then mixing them with partial instructions for creating scientific, folklore, journalistic and philosophical works. The result will be something meaningless that will be difficult to understand. But, first of all, neither poets, nor journalists, nor scientists, nor folklorists, nor philosophers will associate themselves with this supposedly unifying work. In general, nationalism as a term would acquire a more meaningful coloring if it specifically referred to one or another language game. For example, when we talk about nationalism in the context of the language game of Paris or Marseille, we mean Parisian or Marseille nationalism. And we are not talking about protecting or cleansing Paris from foreign elements of the Parisian nation. A language game can perfectly coexist with other codes, since by its nature it cannot be isolated and always intersects or overlaps with another. In this case, Parisian nationalism can play a role only in spreading special skills, habits, discoveries about active everyday life in Paris. Similarly, a Marseille nationalist can promote the history, traditions, and feelings of Marseilles of his environment. It is all about the codes of nations according to which a Marseillaise or Parisian creates and gives meaning to his existence. And it does not matter if each of these nationalists transmits not the entire code, but only a part of it. There can be no instigating, instructive, or demanding function in nationalism, because the language game of the nation is only a means, and a means can only be transmitted and applied.

According to Miller, radical multiculturalism also poses a problem for nationality (43). A multicultural society allows each of its members to define their identity for themselves by finding the group or groups to which they have the greatest affinity. Each group is also allowed to formulate its own authentic set of claims and demands, reflecting its particular circumstances. The state must respect and recognize these claims as equals. The problem is, as Miller notes, that radical multiculturalism mistakenly celebrates sexual, ethnic, and other such identities at the expense of national identities. Multicultural policies also fail to recognize the importance of providing national identities for minority groups that are not yet fully socially integrated into established majority communities. Miller gives the example of the gay pride parade, the belief that gay sexuality should be publicly and politically affirmed. This is an identity shared by many gay activists, but not by many other homosexuals and lesbians, who prefer to consider their sexuality a private matter. The situation is somewhat similar with ethnic and other group identities. Since ethnic identity is usually pervasive, a person does not have much choice about which ethnic group he belongs to. Even if it is not an identity he willingly accepts, others will treat him in a way that makes it clear that they consider him Asian, Jewish, Catholic, black, etc. Citing Harles, Miller provides an example of Americans who were able to avoid the problem of multiculturalism during the process of forming the American nation (44). Today, American national identity has ceased to have any noticeable ethnic content. That is, ethnic groups naturally see themselves as having a hyphenated identity (Irish-American, Asian-American, African-American). In this example, Miller emphasizes that minority groups want to feel at home in the society to which they or their ancestors moved. They want to feel attached to the place and part of its history. Therefore, they need a story that they share with the majority. And this story can be told in different ways and with different emphases by different groups. Radical multiculturalism ignores the need and desire on the part of ethnic minorities to belong as full members of the national community. This ignoring even implies an insistence that minority groups should shed an identity that is considered oppressive in terms of group differences. Under these conditions, however, different groups will not trust each other, which will lead to a lack of social justice in the state. Miller concludes that radical multiculturalists want to affirm group difference at the expense of national commonality, but they do not think enough about how the politics of group difference should work. In this context, I would add that multiculturalism usually distinguishes between an ethnic group and the common national identity of the state, which we have previously defined as mythical. But here the plane of national identities according to the language games of the groups is completely ignored. Why is the Turkish community of the Netherlands proclaimed as separate ethnic group with separate rights and preferences, while the expat community with its special code of nation is considered simply to be a group of foreigners working in Dutch companies? Why are Quebeckers recognized as a separate nation within a united Canada, but Calgarians, distinguished from the rest of the Canadian provinces by their deep roots in Western cowboy culture, are considered simply Canadians? If conservative nationalism ignores the existence of any nations within the borders of the state, then radical multiculturalism is stubbornly built on the principles of ethnic separation, a principle that also does not reflect the real picture of national identity.

In his critique of nationalism and multiculturalism, Miller emphasizes that nationality need not be authoritarian in the way that the conservative assumes. But at the same time, it should not be permissive, as the liberal would like. All that is required of immigrants is to accept the current political structures and enter into dialogue with the host community so that a new shared identity can be formed. States can legitimately take measures to ensure that members of different ethnic groups are included in national traditions and ways of thinking. Here Miller cites France as an instructive example (45). In the nineteenth century, a deliberate policy of “creating French citizens” from the various communities living on French soil was pursued. The two main instruments were compulsory education in public schools and military service. That is, the French did exactly what Miller encourages. They introduced generous immigration laws, while at the same time taking measures to ensure that groups of newcomers were properly incorporated into French citizenship, regardless of cultural origin. Miller adds that France’s national identity has changed significantly over the past century, but this does not mean that the country is now on the verge of disintegration. France has simply acquired a new unifying national identity under current conditions and the passage of time. And here again we will object to Miller. Uniting the French into one mythical nation under the auspices of national symbols and slogans such as “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” is not difficult. In general, this is what every state tries to do to one degree or another. But defining French identity on the basis of more real factors of the nationality of a French citizen than singing the Marseillaise is a completely different story. To say that a Frenchman of Chinese origin considers himself a national brother to a Frenchman of Algerian origin, despite the fact that both may have lived in France for decades, is far from reality. France can by no means be considered a successful model of integrating different national minorities into a single national identity, because many of these communities have a clear awareness of a separate group with different values, that is, a language game. This can be expressed in a special approach to doing business, the need for special shops, the sphere of entertainment, other holidays and everyday habits that are at odds with the national ones. And there may even be a reluctance to speak French, because in their language game French does not play a significant role and is replaced by another language that the majority uses among themselves for basic communication.