6. Chance in the Paintings of Francis Bacon

I don’t draw. I start doing all kinds of stains. I am waiting for what I call “the chance ”: the stain from which the painting will start. The stain is the chance. But if we care about the chance, if we believe that we understand the chance, we will still do illustration, because the stain always looks like something.

Francis BACON (1).

This is how Francis Bacon explains a technique from which the painter can start his painting. When we speak of Bacon’s technique, we are not talking about pictorial technique in the classical sense of the term. In practice, painters usually emphasize the importance of intensity, colors, pace of execution and other characteristics. The Impressionists, for example, reproduce an immediate sensation by decomposing colors. It is the fragmentation of the brushstrokes that makes us imagine the model we want to see. The other characteristic of the Impressionists lies in the search for forms created by light. Rebelling against precision, they try to capture the fleeting impression of an exterior scene. In the case of Bacon, a pictorial technique is based on an instinctive freedom of action. Sketches or preparatory drawings are irrelevant since the painter works from the unexpected. Indeed, Bacon emphasizes that he never had any artistic training and that he was lucky “to never learn painting with a teacher” (2). The systematization and formalization of the artistic approach, in Bacon, is therefore the main danger that kills true imagination. Painters who believe in the importance of the subject are not able to find the real openings. They lack what Bacon calls “technical imagination.” It is always there. The painter must precisely trust the events that happen to the nervous system, created at the time of his creation. When we talk about creation, it is in fact the engine that makes all the instincts work and finds the means to express it in the subject. Yet Bacon finds it difficult to know to what extent this is pure chance or when it is a manipulation of chance. He maintains that if one cannot understand the chance, one can never understand the way in which one acts, that of the unforeseen. It is a major obstacle that prevents us from using all the possibilities that chance offers us.

Despite the great diversity of artistic practices based on chance, I will try to draw a dividing line between them starting from Bacon’s artistic technique. It will be a question of working on the methodical and thoughtful aspect of the use of chance. Then, one could elaborate an artistic value of chance as a criterion of the judgment of taste which rests on a degree of manipulation by chance. In this scale of appreciation, Bacon’s chance will stand out as one of the remarkable models of working with chance on the visual level.

The conditions of chance

We talk about chance when we do not know what will happen and we find ourselves in an unexpected situation. Chance is synonymous with the unpredictability of different eventualities. This is for example the case when I meet a friend at the market, by chance. One cannot, in fact, foresee such a meeting. For Bacon, we can also call luck, accident. The use of the word “chance” in common parlance relates to the meaning of “chance” as a synonym for the absence of cause. However, chance simply expresses an absence of information about the causes of an eventuality. Because of this ignorance and the parameters necessary for forecasting, we can say that chance reflects our ignorance.

In Aristotle, every element has a cause, but chance is not a cause by itself since it is not necessary (3). The scorching heat in winter is an example of the absence of this necessity because winter is naturally a period of cold. As opposed to causes that go without saying, chance is to be classified among accidental causes. The architect is for example the cause relating to the erection of the house. If the house is built by the musician, we can say that, by chance, this house is the work of a musician. Chance is therefore not part of a series of natural elements. It is the result of a mixture of genres: one specific essence and another. The quality of the architect belongs to a series of natural elements, while the quality of the musician to know how to build a house is part of a series of events which depends on one essence but results from another cause.

One can imagine the chains of cause and effect being linked to each other. Yet any two causes may very well be completely unrelated. A fortuitous event or chance appears at the intersection of two worlds of events that belong to independent series. The reason why I met my friend by chance, is related to the moment of the meeting. I belonged to a chain of causes which had no connection with a chain to which my friend belonged. Apart from the events brought about by the combination of sequences, I am unable to observe any series of causes to which I do not belong.

We often use the expression chance when it comes to exceptional and rare combinations. Indeed, Aristotle indicates that chance is not one of the things that always happen, nor of those that happen frequently (4). The regularity of events corresponds to a form of intelligible necessity, that of the law of nature. In other words, events that are finalized or that occur with a view to something, are more frequent than non-finalized events. I do not often meet my friend at the market, since it is not the habit of one of us to frequent this market. So, I go to the market without the will to see my friend at this market. Even if I had this will, I would need a possible end to this will. Even if the fortuitous event has a cause, it is without a final cause in itself. Bacon’s stain is the accident since the result obtained is not repeated and Bacon has no idea of the image that will result. By generating unpredictable stains, he leads his brush without any particular will.

Chance depends on a large number of possible conditions and it is connected with a complete contingency, with the perfect equality of chances which could be destroyed by a superiority of one of the possible causes. One might find that one of these events occurs more often than the other due to an inequality of opportunity. For example, if a die shows the result “3” more frequently, it probably has a symmetry defect. If I meet my neighbor more often at the market than my friend, it is because of an inequality of opportunity which is in favor of my neighbor in the sense of seeing me. He visits the market right next to his house almost every day, while my friend lives on the other side of town. Even Bacon’s accidental stains could be disfavored by his nervous system or the muscles in his hand. Despite the thousands of repeating stains, the cause is Bacon’s specific anatomy. The rarity of events is contingent. Chance is not rare in itself because it represents a possible combination among a number of equally possible events.

Chance in the causal chain

The thesis that affirms that chance has a cause allows us to avoid a rupture in the causal fabric. If we find spontaneity in causal determination, we can find a place for chance in the typology of causes. I will try to find this place in the Aristotelian theory of causality which is a complex metaphysical notion. For Aristotle, there are thus four types of causes (5):

- The material cause that constitutes a thing,

- The formal cause which is the essence of an object,

- The efficient cause which produces an object,

- The final cause which is the goal or end of something.

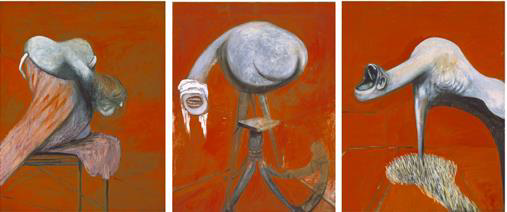

The material cause is defined by the matter of which the object is composed. It can be the clay, stone or metal of a statue. It could also be oil and pastel on this triptych by Bacon inspired by Eshyle’s Oresteia (6).

The formal cause is what is called the form of an object because of its nature. The form of the man is for example the soul since the soul is a faculty which makes it possible to define the man in relation to the statue. The forme of the statue of Hermes is the idea that the artist has of it, that of the resemblance to Hermes. Likewise, the formal cause of Three Studies of Figures at the Foot of a Cricifixion represents certain images that were imposed on Bacon by reading Aeshylus. Bacon imagined the entire crucifixion in which the savage deities who hunt Orestes would be in place (7). These three shapes were to be placed on a frame surrounding the cross.

The efficient cause is the cause of the change. Generally speaking, it is the cause of what changes what changes. For example, the builder who builds the house or the sculptor who carves the statue of Hermes. Bacon, as the painter, also becomes the efficient cause of his paintings.

The final cause defines the reason why an object has been achieved. “Nature does nothing in vain” is Aristotle’s idea that all being has an end, a goal. The house exists to form the dwelling of a family. The cause of being of a statue of Hermes or Bacon’s triptych is aesthetic pleasure. However, the final cause is often difficult to distinguish from the formal cause, especially when talking about a necessity, an emergency. Bacon’s desire to paint the triptych after reading Aeschylus is not the final cause, but rather a conditional necessity of beings subject to becoming. Contrary to Bacon’s desire, which is not the real cause, the pleasure taken in imitation and representation is the absolute and pure end for which the triptych was painted.

The spot from which Bacon acts plays a paradoxical role in this chain of causalities. On the one hand, we can say that the trace left by a coloring is an element of material power, as well as the drop of cement that the builder of the house leaves on the bricks. Accidental stains also catch Bacon’s determined stains like cement joins bricks. The combination of stains with colors generates the design like the clinging of bricks with cement produces a house. In this case, the accidental stain is the immanent matter of which Bacon’s triptych is made.

On the other hand, the accident appears as a pictorial technique based on the unexpected. It is the knowledge of artistic creation that Bacon employs to obtain an unexpected result. It follows that the accidental stain is the efficient cause which does not depend on the desire, belief or intention of the creator. It possesses in itself the force necessary to produce a real effect, that of the resemblance to the trait that one would like to retain. The conjugation of the consequences with the subject is the art of Bacon which materializes in a permanent balance, that is to say a game between pictorial accidents and particularized things. It is a medium without which Bacon could not invent his new forms.

Finally, we discover that the stain changes the form that configures Bacon’s drawing. Even if Bacon imagines his subjects inspired by books or paintings, he exploits the chance as a principle of birth of the image. The original subject changes through the instinct that works outside of laws and systematization. This instinctive way brings out on the canvas the unexpected which constitutes the new basic subject.

…The other day I painted someone’s head, and what made the eye sockets, the nose, the mouth, they were – if you analyze them – just shapes that have nothing to do with eyes, a nose or a mouth; but the movement of the paint from one outline to another gave a resembling image of this person I was trying to paint. I stopped ; I thought for a moment that I was holding something much closer to what I am looking for. So, the next day I tried to push it further and make it even more poignant, even closer – and I lost the image completely (8).

In the beginning, Bacon has an idea of form but does not know how form can be materialized. For Bacon, the form of primary realism as illustration is boring. He walks the tightrope between figurative painting and abstraction to trap reality. By chance, he wants to arrive at the foreshortened sign of the body instead of the illustrative body. In this construction of the painting, Bacon knows what must be accepted or destroyed, eluded or specified. Therefore, the image takes on a form that has nothing to do with a mental image. This explains, for example, why Bacon never did his Three Studies triptych… as it had been previously conceived. The three original forms were left as sketches.

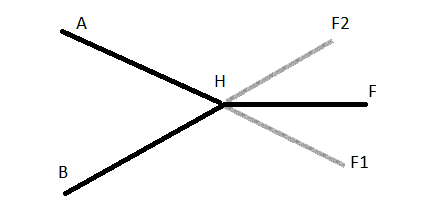

Thus, if the stain is an accidental cause in things that happen in view of an end, this cause calls into question the final goal by modifying the formal cause. We can resume the causal chain which after the intersection with the fortuitous event, changes the direction as an end. The graphical representation of this image is as follows.

We see here:

A – the causal chain of Bacon’s artistic process,

B – the causal chain of chance,

F1 – the intended purpose of chain A,

F2 – the intended purpose of chain B,

F – the current purpose,

H – the intersection of the chains.

Purposes F1 and F2 are the results for which things are done. If Bacon never used accident in Three Studies…, he would paint the cross in the center of the image (F1). Also, monstrosities wouldn’t be so crisp and poignant. Consequently, the final cause as a principle of work generation was different. Bacon would express it simply by representing objects of external reality. If Bacon always painted his triptychs by accidental stains without particularization of the features and without subject, he would do anything. He would then arrive at pure abstraction or decoration (F2). When the accident crosses the causal chain (H), particularized objects are modified by something completely irrational. Therefore, the shape changes into a new, unexpected shape (F). The question that arises is whether the purpose F is:

- a restitution of the F1 purpose,

- a restitution of the F2 purpose,

- or a purpose which is totally different in nature to F1 and F2.

Aristotle distinguishes two kinds of beings: beings that are by nature and others by chance. When F2 is totally constructed from accidental causes, it is artificial and unnatural. Consequently, the restitution of F2 by F is impossible, since F is a goal by itself and does not have the same nature at all. The finality of F1 passes through the same figuration as F. It is as necessary and constant as F, and therefore shares the same nature. However, there is a key difference between the two. In F1 the pictorial act is reduced to unequal probability. In other words, the painter has a clear idea of what he wants to do. In the case of F, the painter has the same data, but he wants to abandon this idea to get out of the cliché. He knows what he wants to do, but he doesn’t know how to get there. Now, being a type of action without probability, the accidental stain gives the painter a chance, a chance between equal and unequal probability. Thus, chance does not change the nature of F, but it helps to get out of the canvas and to arrive at the goal. We can therefore say that F is the figuration found in F1, when the random manual mark is an instrument that the painter uses in the pictorial act.

Manipulation by chance

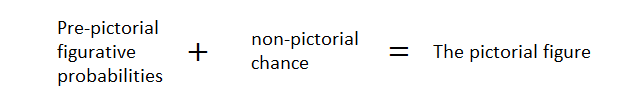

Bacon’s accidental marks mean nothing with regard to the visual image. Indeed, Gilles Deleuze adds that they themselves are only valid to be used by the hand of the painter (9). Chance, for Bacon, is therefore necessarily manipulated chance, chance integrated into the creative process of painting. On the one hand, we have a choice of probabilities. These are figurative data, the pre-pictorial clichés in our perceptions, memories and fantasies. On the other hand, we find chance, which on the contrary designates a type of choice. If an artist’s data were an object, they would be a die for the painter to roll. When the painter invokes chance in his game, he throws a dice in such a way that he makes a complicated choice. We can, for example, imagine a die that shows 2 sides at the same time since it has been thrown to the side. With each stroke, a dice on the side expresses a non-pictorial choice on the canvas. In order for this choice to become pictorial, Bacon reorients the spots to the sign and, consequently, he extracts the improbable figure from the pre-pictorial probabilities. Thus, the Baconian formula of the pictorial act is the following:

Here the problem that arises is whether the chance is, in fact, manipulated and integrated into the act of painting in the Baconian way. On this subject, Deleuze constructs two fine examples which oppose Bacon to the fact that we do not see the distinction between chance and probability (10). First of all, Deleuze confronts Bacon with Duchamp who also discovers the creative potential of chance. One of the works in which Duchamp incorporates his idea of chance is Three Stoppages-Standard.

Here Duchamp retains an experience of chance by deforming the rules according to accidental curves. More precisely, he released a thread, constituting the design of the curves according to which the rulers were going to be cut. What Duchamp wanted to emphasize is the arbitrary character of the standard meter, a symbol of the irrational. It is a reality of Duchamp which joins with the infinity of possibilities thanks to chance. However, the infinity of possibilities for Bacon is simply the dispersion of probabilities. Duchamp also works in the field of facts, the field of phenomena, while Bacon exploits the field of the improbable. Duchamp plays on the relationship between original determination and pre-pictorial possibilities, while Bacon plays on the relationship between determination and indeterminacy. Duchamp fixes the probability, but Bacon produces it. Thus, Duchamp’s artistic process is not part of Bacon’s act of painting since there is only one set of probabilistic data.

Another example shows the volume of misunderstanding of those who talk about chance and Bacon. It is about an example of a cleaning lady who is also capable of making accidental marks. Yet when she is involved in an act, she just makes non-pictorial marks. There is no manipulation in this act, or rather the reaction of manual marks on the marks of chance. Therefore, the cleaning lady’s hazard does not become pictorial because she cannot use it. Indeed, Bacon points out that the painting of the world, especially abstract painting without the subject, is “at a very bad time” (11). Painters try to paint only with the strength of matter. They throw material on the canvas and immediately find the features of the character. As a result, without will, the paintings arrive at an immediate state of character that is outside the illustration of the subject. On the contrary, what they must do is not to end with the accident, but rather to end with the freezing of the force in the subject. To capture the origin of the idea in the chaos of possibilities, it is the technique that must arrive after the accident.

Bacon’s canvas is a field of leakage and connections. Bacon first of all has a radical hostility to the clichés that already occupy the canvas before the beginning. Clichés are everywhere. These are the narrative or illustrative reproductions that we always see in the photos. Although Bacon is fascinated by photos as means of seeing, he only recognizes in photography an artistic power. He does not integrate the photographic image into the creative process since it is too dazzling and too figurative to be felt. Consequently, Bacon wants to abandon the photo and the clichés that crush the sensation (12). However, the fight against clichés does not imply their pictorial deformation. Deformation is never just form. Even in abstract paintings, reactions against clichés reproduce clichés. The painters use the same pictorial techniques to distort the clichés and, therefore, they end up with the same act of painting. For Bacon, rejecting clichés means accumulating them on the canvas before work begins and then exiting through the manipulation of marks at random. By exiting, Bacon does a work of connection that tears the pre-pictorial visual whole from the finally pictorial figure. He liberates the figure, captured in the cliché, by chance. While the chance produces the multiple elements such as lines and accidental marks, the sensation towards the subject connects this multiplicity. Consequently, all the different movements are constructed on the level of sensation alone. What Bacon generates is therefore the possibility of exit from possibilities.

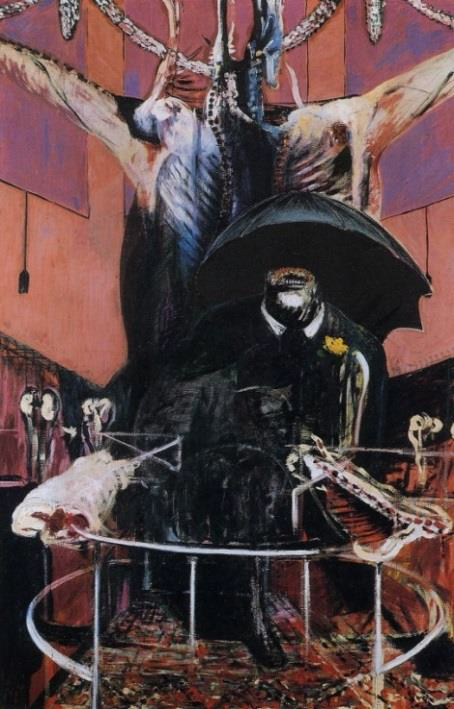

Bacon’s figure is the sentient form which has a face towards the subject on the personal nervous system (13). This is what is more important for Bacon since sensation builds true imagination, out of clichés and spontaneity. However, the production of the figure for Bacon is not a controlled progression. The sensation does not pass gradually from one form to another by the modification of the pre-pictorial data. It can pass from an intention to a figure by the surge of vigor in the production of a chance. In this regard, Deleuze takes the example of “Painting” from 1946 in which Bacon wanted to make a bird. However, the insubordinate stains intervened in the pictorial act and suggested the quite different figure, the man with the umbrella. This does not mean that the bird suggested the umbrella, but that the bird which still exists in Bacon’s intention suddenly suggested the whole image. It is not about the deformation, but rather about the anomaly of the accident in all its violence. Thus, the vigor of the chance would be the guarantee that Bacon could avoid the formal in order to produce the Figure. With the intention of producing a bird, Bacon makes an explosion of the pre-pictorial data by the explosive accident. It explodes the structuring to open up the possibility of destructuring. With violence, the accidental stain ruptures the tissues, tears the mouth, the face. It cuts out the lines at random and mixes this mixture. However, in this movement of destructuring, it is necessary to preserve the structure without falling into the incomprehensible. It is not a question of completely controlling an accident, but of directing it so that original forces spring from the result. It can be said that it is not by accident that Bacon painted the umbrella, but that he produced it unconsciously via an intention. It was a test gesture of the unconscious which both fails and at the same time wins. In this act of painting, the chance is what connects intention with instinct. It provides favorable conditions for the unconscious to express itself.

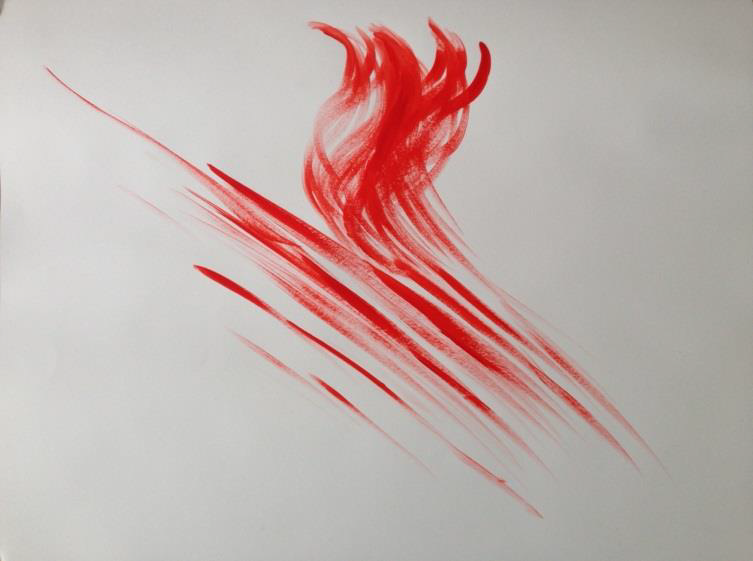

When the effectiveness of the manipulation of the accident obeys an instinct, the result does not depend on a conscious will. Painting is not an act of expected realization, but the struggle between the chance and the unconscious which chooses or crushes the accidental stain. This is why the manipulation can fail and this failure is difficult to explain. We cannot account for this unconscious struggle to develop the pattern that always works. We can just try again and again until we reach the result, the successful Figure. When I paint the painting about emotion like Pride based on random stains, I have the same experience of manipulating chance (14).

Too much will and the drawing becomes banal. Too much spontaneity and everything ends up in pure confusion, chaos. Chaos must remain localized in space. It is essential for something to come out of it, but it blurs the picture if nothing comes out of it. Therefore, one must be semi-conscious to unconsciously work on random spots, but at the same time to consciously control all accidental connections. It is perhaps more a question of sensation than of technique since the manipulation of the accident is the result of a certain arrangement of circumstances. However, the expression of the unconscious which realizes the progression is already a technical step, at least sensational. The talent of the artist intervenes in the act of violence guided by the unconscious to capture the Figure. The artist must always have the idea of what will allow him to get out of this uncertain outcome. In the aim of the irruption, it is the sensational lines that must seize an opportunity within the possibilities of the connection of the will with chance. The manipulation of chance in the pictorial act therefore makes possible a point of the emergence of the sensational Figure.

Chance as a method

As part of the method, reflection on chance in art is a crucial issue since it always corresponds to indetermination and chaos. How can chance as a method be a perfectly considered notion? In her philosophy thesis, Sarah Troche proposes to restore the issues inherent in the methodical use of chance in 20th century art (15). The notion of chance is approached in 3 dimensions:

- the practical dimension concerning the methods used by the artists,

- the theoretical dimension to formulate the specificity of the artistic thought of chance,

- the critical dimension corresponding to the transformation of certain fundamental notions of aesthetics.

The problematization of the notion of chance

The first question Troche addresses is to what extent chance is actually present in the work. This is the problem of the tension between chance and choice. For example, when we talk about Three standard stops, we can assume that Duchamp’s choice plays a decisive role in the acceptance or rejection of the results obtained. Therefore, chance loses its random significance in the act of creating this work. When there is choice, chance is necessarily limited. Conversely, pure chance leaves no room for choice. Chance is therefore caught in a contradictory game between control and absence, order and disorder, mastery and unpredictability.

To overcome this problem, Troche poses the articulation between choice and chance as the principle of the use of chance in art. A game of chance may be the closest model to the artificial creation of chance. When rolling dice, the player’s choice does not harm the randomness of the outcome, but it does make chance possible. The player plays with perfectly known chance data: heads or tails. But he cannot predict whether the outcome will be heads or tails. In this case, while the random result is always different, it is part of the act of the player who is never anonymous. The player can explain by what process the risky act is organized, who produces it and to what end.

Artists also work with chance data allowing them to think about chance from a precise technique. We must therefore perceive chance as an experiment perfectly thought out by artists. John Cage’s Music of Changes, for example, illustrates this use of chance as a real listening exercise. Cage uses chance deliberately to gradually modify our relationship to listening to a sound object.

The delimitation of the corpus

The second difficulty of the method that Troche tackles concerns the question of the limitation of the corpus. How to select works that represent a whole set of possible examples in all disciplinary fields? If we tried to draw a dividing line by discipline, we would see that works belonging to the same discipline (music, painting), and for which the artists used chance, are not necessarily produced by the same method. To bring together this great diversity of practices, Troche decides to rely on an important dividing line between two types of use of chance: methodical chance and the aesthetics of accident.

Methodical chance is a set of relatively simple and shareable operations. One can also think of the game of chance whose rules are perfectly formulable. In Cage’s Music of Changes, for example, it involves dragging musical notes so that the melody becomes discontinuous. Similarly, we can redo Three Standard Stoppages, by dropping a one-meter-long thread to the ground from a height of one meter. Opposed to methodical chance, the aesthetic of the chance escapes the control of the artist. By exploiting the stains, this practice is always expressive and indeterminate. The strongest example is that of Pollock’s painting, which designates the triumph of formlessness. Pollock’s manual traces are the product of multiple coincidences that escape any law.

To show this contrast between methodical chance and accidental aesthetics, Troche opposes term by term the thought of chance in Dubuffet to that of Duchamp. Dubuffet’s chance is necessarily manual, guaranteeing the expressiveness of the result. Conversely, Duchamp wants to forget the hand, since it is itself subject to chance. Therefore, in order to construct a work of pure chance, it must be produced mechanically and with precision. However, Troche refers to François Morellet who opposes what he calls the warm hand to the cold hand of an artist. The warm hand refers to the artist who sacrifices the origin of his work for the sake of brilliant expressiveness. The cold hand, on the contrary, acts by following a system which represents the artistic choices during the execution of a work. By restricting the corpus to methodical randomness, Troche admits that there always remains a great diversity of possible practices. In order not to erase them, she proposes to group the different cases at the level of the purpose of the use of chance, always responding in the artist to a particular problem. Within three paradigms, Troche distinguishes:

- chance and memory,

- chance and invention,

- chance and silence.

Chance and memory refers to the method of exploiting biological and conscious memory. However, Troche wants to group under this paradigm all the works of surrealism, including the works of Max Ernst and Breton. Surrealism is based on processes of creation and expression using all the psychic forces freed from the control of reason. In this, chance plays an important role by participating in the disinterested game of thought.

Chance and invention correspond to the combinatorial forms of chance. The works of François Morellet, for example, represent the game of the intervention of chance and the basis of mathematical equations or numerical systems. This theme is therefore characterized by the invention of new forms and creative games in which the rule governs the development of a work.

As for chance and silence, it is an approach that puts at a distance the criteria of taste or the logical categories that structure our perception. The examples of Music of changes by Cage and Three Standard Stoppages by Duchamp can be enlightening. By preserving the data of chance, these works transform our mind. In other words, they make us sensitive to a form of sonic or visual complexity that cannot be reduced to the usual structures of the language game of art. However, chance is the privileged means of this transformation of the mind. To accept chance is therefore to displace the norms and evaluate them in a space where the central points interfere at all times.

The problematic points of the corpus

In this context, I want to question the grouping of artistic practices through the random processes proposed by Troche. At the outset, it should be noted that the corpus is not completely reducible to these three main themes. There are still other practices whose purpose of using chance differs from the purpose of one of the three paradigms. Pollock’s abstract paintings, for example, do not belong to any group. They are neither related to the exploitation of memory, nor to the invention of forms, nor to the change of perception. Pollock follows no rules since he wants to liberate the line from its representative function. He lets accidental stains emerge to achieve “…total harmony, easy exchange” (16).

To raise the following difficulty, we must think about the specificity of artistic work with chance. If we approach chance through the finality of a work, the singularity of the random act of the artist vanishes in the field of art. Apart from chance, there are a wide variety of means capable of modifying our relationship to art or of inventing new forms. Artists, while under the influence of LSD, hypnosis, dreams and other altered states of perception can pursue the same goal as the artist who employs chance in his work. If we want to formulate the specificity of chance in art, it must necessarily be characterized by the relationship between the artistic choice and the random act. This brings us back to the distinction defined by Troche in the delimitation of the corpus.

The distinction between methodical chance and the aesthetics of accident poses a problem corresponding to art criticism. The term “the aesthetics of the accident” already implies the value on which we pass our judgment of taste. The warm hand always refers to the figure of genius. Conversely, methodical chance assumes that it is not part of aesthetics, since it is not part of visual expressiveness. The cold, mechanical, regulated hand refers to the external force that cannot be fully appreciated as an artist’s gesture. However, we can judge a work of methodical chance from the conceptual criterion, the strongest example being that of the accidental purity of Three Standard Stoppages by Duchamp. This work can please or displease with its conceptual idea imagined by Duchamp. Similarly, we can infer the possibility of an aesthetic character from the idea of Cage’s Music of changes, which refers to the change of rules within the language game of music. A central notion in John Cage is that of indeterminacy that must be thought of in a positive way. It is music that leaves room for chance, but which remains organized and precise. Consequently, methodical chance also relates to the aesthetic dimension through the origin of a work, namely through its concept.

Next, the difference between the “warm hand” and the “cold hand” is not always applicable to the opposition between methodical chance and the aesthetics of accident. Troche defines, for example, the surrealism of Max Ernst as a practice of methodical chance. Yet even though the frottage that Max Ernst used in his paintings is shareable and precise, it does not rely on definite data. For this technique, the artist lets a pencil lead run over a sheet placed on any surface, without having the slightest idea of which more or less imaginary figures will appear. Each frottage gives the inanimate object a different meaning. This leads to a contradiction since methodical chance is not defined as a set of unique and unrepeatable circumstances.

The problem with the partition between methodical chance and accidental chance is that it does not take into account semi-automatic processes, that is to say artistic techniques which involve the two aspects of chance as we see them in the surrealism by Max Ernst. Besides, there is a kind of process which is too distant from methodical chance as it is from tachism. Francis Bacon’s method, for example, is given in a vague and incomprehensible way. We can start like Bacon by drawing an accidental stain, but it would be practically impossible to act on this stain in a Baconian way. On the other side, Bacon expresses his desire to avoid formlessness through chance in order to arrive at the Pictorial Figure. This is called the manipulation of chance, which refers to the balance between order and disorder. Music of changes and Three Standard Stoppages, on the other hand, do not fall under this process since Duchamp and Cage do not manipulate chance, but simply fix accidental probabilities. As far as Max Ernst is concerned, he does a kind of manipulation, but does not rely on pre-pictorial ideas as Bacon does.What matters, therefore, is to what extent the manipulation of chance is present in the artistic act, from what pre-pictorial data the artist begins and to what end he produces. It is at the level of these questions that we can group the different practices. The table of this grouping would be as follows.

| Form | Formless | |

| Manipulation by chance (the pre-pictorial idea) | Bacon | |

| Manipulation by chance (the absence of a pre-pictorial idea) | Ernst | Pollock |

| The absence of manipulation (the pre-pictorial idea) | Duchamp, Cage | |

| The absence of manipulation (the pre-pictorial idea) |

Here, the grouping of works was built at the intersection of two axes: the result (the form and the formless) and the manipulation of chance (in connection with the pre-pictorial data). In this case, we not only inscribe the specificity of chance in the artistic gesture, but we also make possible the elaboration of hierarchies of values between works that would be more or less hazardous. This is to elicit comparisons and highlight points that deserve attention. However, what constitutes value is a criterion that serves to describe a “hazardous” relationship between the artist and his work, to classify them into classes. If we posed manipulation by chance as a criterion of the judgment of taste by being on the side closest to genius, the evaluation of chance in art would be quite possible. In this case, the appreciation of a random work results in the definition of the degree of manipulation of the artist. The data before the beginning, the act and its effect elaborate the new non-aesthetic dimension on which we can carry our aesthetic categories. This approach allows us to avoid pure subjectivism in aesthetic judgment within the language game of accidental works. It is in this sense that one can put forward reasons for or against the work each time in question.

Conclusion

Historically, the use of chance in the pictorial act appears as a reaction to figurative painting. While figuration accounts for mere mimesis, the manipulators of chance continually employ a painterly feel in every dot, stroke, and form. However, these are not the figures of chance, but rather the signs towards infinity without falling into chaos. The Baconian accident appears in pictorial creation as the motor that provokes sensation, acting on the unpredictable. It is also the artistic instrument with which the painter blurs the tracks to make a new start.

Finally, the chance is the material from which the Figure is produced. In this creative process, the chance stands in the way of a bad representation, a false image, a cliché. However, the desired figuration arises in this permanent struggle between free marks and instinct which is transformed into voluntary movement. The chance is power itself. It disorganizes and deforms. It gives a disoriented vision in all the pre-pictorial plans to exploit something that is not illustrative. When chance is an external force that comes to thwart the cliché, instinct tells Bacon the direction to take. This act is the seizing of the manipulation of chance and of the opportunity to bring forth the Figure. It follows that all of Bacon’s painting is a degree of accident: pre-pictorial accident, transformed accident, figurative accident, manipulated accident. The charm of his painting thus lies in the figuration of the unconscious which makes the Figure embody a field of accidental anomalies. It is the unpredictable emergence of another world through non-representative and non-narrative traits that open the way to the expression of the unconscious. Bacon imposes presence under forms, under representation. This reality is not a narration of the fact, but an intensity of the movements of life. By observing the agitation of these movements on the flat, Bacon touches the fact as closely as possible. He therefore makes the deformed, distorted, blurred Figure pass in a more precise way.

By distorting the thing, Bacon leads to recording of appearance and this allows him to remove too much absoluteness and too much truth from the image. He approaches the sensational face resting on the base of the structuring. It expresses contingency by releasing the anomalous Figure. Bacon’s Figure is therefore an anomaly of possibilities, a connection of contingency without any necessity.

This means that Baconian painting is not in the field of mechanical or technical process, but in the field of tension between intention and sensation. Handling accidental stains cannot rely on code or caution. It accounts for magical meeting points, random marks and will. Therefore, sensational painting is a risk to be taken with a manipulative play. There is no layout necessary. This play of the artist’s sensation with an accidental force admires by this sudden appearance of the unpredictable form, a possibility freed from the chaos of indiscernibility. It can therefore be expected that the artist of the future will continue to apply the manipulation of contingent marks in his artistic creation where he will establish a new medium of sensation to obtain the unexpected and happy result.

References:

(1) Francis BACON, « Entretien Avec Francis Bacon » (La Quinzaine littéraire, 1971), in Marguerite Duras, Outside (1984), Gallimard, Folio, 1996, p. 333.

(2) Ibid.

(3) ARISTOTE, Physique, 196 b 23.

(4) ARISTOTE, Physique, II, PH19a18.

(5) ARISTOTE, Métaphysique, I, Chapitre 3.

(6) Françis Bacon, Trois études de figures au pied d’une crucifixion, 1944.

(7) David SYLVESTER, L’art de l’impossible – Entretiens avec David Sylvester, p.218.

(8) David SYLVESTER, Entretiens avec Francis Bacon, 1962.

(9) Gilles DELEUZE, Francis Bacon, Logique de la Sensation, op. cit., p.89.

(10) Ibid. p. 90.

(11) Marguerite DURAS, « Entretien avec Francis Bacon ».

(12) Gilles DELEUZE, Francis Bacon, Logique de la Sensation, p.87.

(13) Marguerite DURAS, « Entretien avec Francis Bacon ».

(14) My acrylic painting in 2014

(15) A meeting around Sarah TROCHE’s thesis, « L’aléatoire dans l’art du XXe siècle : Marcel Duchamp et John Cage », dans le cadre du séminaire « Questions d’Esthétique », Le Centre Victor Basch, Université Paris-Sorbonne, 20 novembre 2014.

(16) Through these concepts, Pollock emphasizes the unconscious nature of the act of painting. See Eric, CHASSEY, “Jackson Pollock figuratif ou abstrait ?”, L’Oeil, no.504, mars 1999, p.55.