Ethics of the whole

In this paper, I will observe if we can apply classical ethical concepts to the whole and if humanity is able to judge its actions on a holistic realm. More precisely, I will see if Mill’s utilitarianism and Kant’s deontology can be applicable in justifying actions based on unity and integral wholeness. For this, it will be necessary to define the holistic ethics and how it differs from those of traditional moral theories.

Mill’s utilitarianism consists in justifying actions by producing happiness and reducing its reverse. So, if somebody believes that his or her actions adds to the greatest happiness of the greatest number, then his or her actions are justified. Even using somebody as a mere means that is killing, cheating, coercing, lying is admissible if your actions increase the greatest good. We can take a classic example in which the Nazis declared that they would burn all the village if the inhabitants did not reveal where the commander was hiding. The inhabitants handed over the commander to the Nazis. The end of the story is that all the inhabitants are alive and the commander is dead. Even though the commander was used as a mere means, this action of the inhabitants is justifiable according to the Utilitarian principle. By sacrificing only one person, the whole village was saved which produced the greatest happiness of the greatest number. Several questions arise when we review this conclusion from the holistic perspective. How the village know that its decision really produced the greatest happiness? How they estimated that this greatest good would affect the greatest number of persons? If we defined the village as a whole, then we could answer affirmatively that the village was right in its calculations. However, the village is not a whole, but a part of it. It is a part of a region, which in turn is a part of a country. The country in which the village is situated can also be a part of the union of countries. Finally, the unions of countries compose the world. Saying that inhabitants of the village added or not to the greatest happiness of the greatest good becomes absurd as it is just out of the scope of everybody who could try to calculate it on a global scale. Moreover, if we take into account a long-term effect of the consequences of the action of inhabitants, we can arrive at totally contradictory suppositions. The revealed commander who was killed by the Nazis could be the real savior of the nation. If he was alive, he could save several hundreds of thousands of lives, which does not justify the action of inhabitants based on this supposition. It could be also that after winning the war against the Nazis and saving hundreds of thousands of lives, this commander later would start a war against the Nazi’s allies, which would cause millions of deaths. So, now it is more justifiable to say that inhabitants were right in handing over the commander. Inhabitants were not only saved, but they also saved millions of lives. That is the problem of the Utilitarianism as it completely falls apart when we try to evaluate the effects of the consequences of our actions more globally in terms of space and time.

Compared to Utilitarians, Kantians should not count what contributes more in the greatest happiness. Kant introduces a categorical imperative which represents an action as itself objectively necessary, without regard to any further end: You ought to do X. The principle of the categorical imperative is as follows: Act only on that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law. The second version of the categorical imperative states: Act in such a way that you treat humanity not using your own body or any other person merely as a means. The categorical imperative leads us to the maxim, that is subjective principle of action. It works like that. Take any possible case of human relation, in which one has to decide his/her behavior, in the general form A does such and such a thing to B. Now the moral question is “Should A do this to B?” According to Kant, A’s answer cannot depend on A’s pleasure, or desire or utility but rather A has to give an abstract general sensible account of his/her situation with reference to B and then work out a general rule of how anybody in the same situation ought to behave. A cannot treat B as mere means that is using B as a device without agreement. This is a maxim. To put it more simply, when I want to decide if my action is ethical, I should imagine if everybody in the world does it and does not use any person for one’s own purposes. Then I should wonder if I would want to live in such a world where this action is considered as a universal law. If not, then I give up on this action. In the forementioned case of the village and the Nazis, Kantians would probably say that it is more morally justified to burn the village, as handing over the commander would mean using him as a mere means for a survival of the inhabitants. Another example shows clearly a discrepancy of the Kantian’s moral doctrine. It’s 1939, and you’re hiding Jews in a cellar. The Nazis come to the door and ask you if you’re hiding Jews in a cellar. Should you lie to the Nazis? Kantians would say that I should not lie because a lie is not morally justified according to the maxim which obliges us not to use persons as mere means. But Kantians could also say that Kant meant to apply the universal law to each specific maxim. So, I should ask myself if I could live in a world where everybody lies to a killer. If yes, then my lie is morally justified. Even if this case is exceptional, it shows a breach of the doctrine which can be used by critiques to say that in the end the Kantian moral theory is just a disguised Mill’s utilitarianism. If I lie to save somebody and it is morally justified for Kantians, then what Kantians do is just producing the greatest happiness of the greatest number of persons regardless of using somebody as mere means. Moreover, as soon as Kantians take into consideration what precedes an action and what can follow after it (the Nazis are looking for Jews to kill them), then applying categorical imperatives becomes even more confusing. What if you’re hiding Jews involved in organized crime, and some of them are murderers or what if you`re hiding somebody who can potentially start a nuclear war and cause millions of deaths? Here, we should specify a universal law even more. “Can I live in a world where everybody lies to a killer?” should be extended to “Can I live in a world where everybody lies to a killer of Jews who are murderers” or “Can I live in a world where everybody lies to a killer of a person who will be responsible for millions of deaths?”. The more Kantian involves an antecedent or a consequent of the action in the judgement, the more particulars should be specified in the universal law. In this case, the universal law not only becomes less universal and more specific, but also makes judgement more conditioned by one’s awareness of antecedents and consequents of an action. How can we judge your action if, for instance, you’re not lying to a killer and tell where Jews are hidden, but you are not aware that you are telling the truth to a killer? Or you’re lying to a killer who wants to kill a serious criminal you’re hiding, but you are not aware that you’re hiding a serious criminal?

So, it is difficult to deal with a Kantian maxim so that everybody would will the same to be it a universal law and it is difficult to make a judgement on such action. Returning to the example of the village and the Nazis, Kantians could justify both choices leading to opposite consequences. One would say that he would live in a world in which inhabitants of the village show extreme courage and heroism by sacrificing their lives in the name of saving the commander. Others would object that he or she would prefer the world where the lives of civilians are more valuable than the lives of the military. Or let’s take a do-gooder who is against smoking. He or she is running around taking cigarettes from the mouths of people, passing out anti-smoking pamphlets. For some, this would sound ethical since they would be fine if everybody in the world had anti-smoking attitude. For others, especially smokers, this is morally unjustified. They would accept a universal moral law by which nobody restrains somebody from smoking. As we see, the Kantian’s doctrine can be less reliable than Utilitarianism if we need to define exactly how we ought to behave so that our actions be morally justified in terms of categorical imperatives. Utilitarianism is criticized that it links morality with happiness or pleasure while happiness is subjective and can vary from experience to experience. However, categorical imperatives are also conditioned by a person`s picture of a harmonious living among human beings as ends in themselves which complicates a choice of the moral law. On the one hand, Kant`s deontology sets a brilliant self-defense against an infringement of human rights and personal intentions. You feel right away that something is intrinsically wrong when human beings are used as mere means and not defined as the ends in themselves. On the other hand, it is questionable if Kantians give the same abstract general sensible account of the moral action. In addition to this, Kantians cannot be sure in what they imagine as the world where a particular moral law is applied. Living in a world where nobody restricts smoker’s rights seems to give a clear image of how this world would look like for a moment. However, this image could be wrong on a long term. Imagine that this moral law would increase the number of smokers to such an extent that countries would impose much more heavy restrictions on smokers. Similarly, those who would consider that the world is better when smokers of the whole world are annoyed, could be mistaken. For instance, this measure could provoke worldwide clashes between smokers and non-smokers to such an extent that those who was in favor for annoying smokers could change their mind. Taking an example of a liar to a killer, who can be sure in what this moral law would cause as a consequence? Would this save more victims or instead would provoke more deaths? If a liar manages to fool a killer, then it seems to be a good consequence. However, a lie can also cost a life to a liar which leads us to a bad consequence. We return to the same problem of utilitarianism, which depends on the consequences of effects of actions on the greatest good, and its application is impossible on the long term. Kantian deontology depends as well on the consequences of effects of actions. Even if a categorical imperative is based on an action as itself objectively necessary, without regard to any further end, we should be aware of the consequences of the moral law we apply so that we achieve the harmonious living of human beings as ends in themselves. In this regard, predicting the consequences of Kantian moral laws seems to be as well complicated as that of predicting utilitarian actions on the long term.

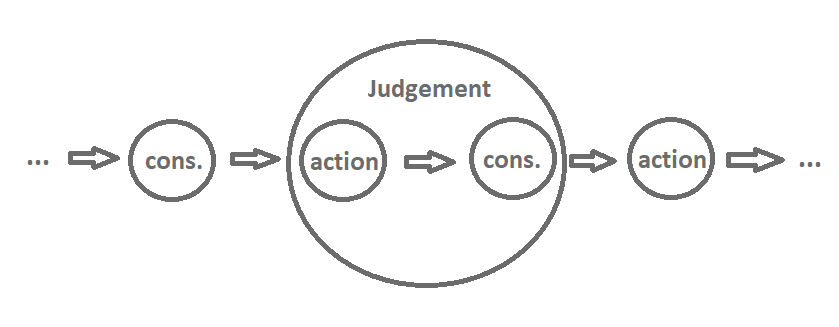

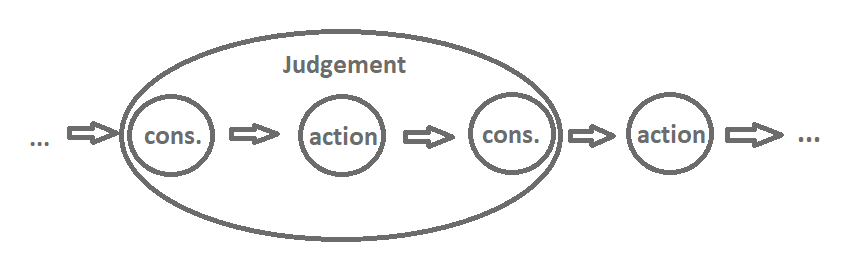

It comes out that both classical moral doctrines are applicable only to an isolated case in space and time. We pretend that our particular case either represents the whole or the whole consists of the same cases. In this sense, we judge an action based on immediate consequence and stop at it as if nothing happens after that. This is actually a problem of all the ethical theories which are based on reductionism in the complicated nature of human affairs. Indeed, moral decision-making is such a complex process that any theory still cannot avoid conflicting situations in the development of the ethical guidance. What guides us today is just a hybrid of utilitarian and deontological approaches on a short-sighted basis, pretending that our judgements are concerned about the consequences in the future. We could try to apply utilitarian principle of utility and categorical imperatives to the wholeness of natural things, but we could not. It does not make sense for a man to figure out what really caused a particular action and which final consequence it will produce in the causal chain of events. For example, when we praise somebody’s achievement, we do not take into consideration what could happen before and what will happen after this achievement. It could be that this person does not deserve a recognition. This achievement may cause such bad events that would completely overlap what has been achieved. It is also possible that if this person did not achieve something at a particular moment, he or she would achieve much better results later. So, it would be better if this person did not achieve it at the moment. Similarly, we can say that what has been achieved does not deserve much respect as this person could achieve better things earlier, but failed because of bad actions. Reversely, someone’s bad action can be a precursor of a good consequence later or what someone did is the best thing he or she could do out of all the possibilities. If he or she did not do this bad action, we could expect much worse results. If John does a terrible thing to someone, we will isolate this event from the causal chain of an action and a consequence and will judge it as a bad conduct.

Sometimes, our judgement will be based on an extended coverage of the causal chain.

The problem is that we could never embrace all the causal chain of events to make a judgement on John’s action. It is not only about a linear reduction, but also about a vertical one. We can never be sure that we took into consideration all the causes or all the consequences of an action. We can just consciously ignore some of them, we can forget about them or we can just not know about them.

As a result, any of our judgements based on consequences of an action are meaningless, since a man is unable to perceive the whole chain of cause and effect in relation to an action. Morality should be grounded on the wholeness and this is what involves holistic ethics.

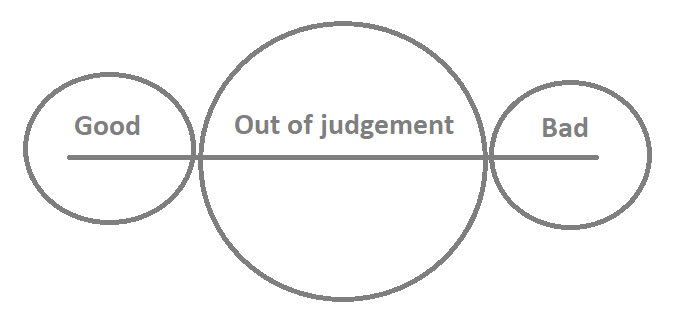

The perception of the whole is multifaceted. First of all, it is based on removing of the abstract separation of the finite and the infinite. These are not entirely opposed and incompatible, but are moments of wholeness. The whole is truly possible only when it is momentary. Hegel gives an example of the infinite returning again to the finite. If bad infinity is a line, then good infinity is a circle ending in its own beginning. Infinity becomes finitude when they are simply moments already contained within each other, inseparable. Secondly, the contemplation of the whole is placed in a context of absolute simultaneity, for example, when the imagination tries to contemplate both globally relevant events and trivial moments in the whole. Furthermore, the whole multiplies the known by an infinite multiplier, that is allowing maximum possibilities of life experience and memories related to it. Finally, the simultaneous contemplation of events of the whole ignores causality. Within this perception of the whole, moral acts are not performed for the sake of distant consequences, but rather out of a sense of doing something whose intrinsic value will be considered as good through countries and generations. Similarly, immoral act is qualified as immoral because of its intrinsic value that may be perceived as bad through space and time. So, a moral act is rooted in the good of the whole, while an immoral act is grounded on the bad of the whole. As long as we perform an act whose intrinsic value may seem relative, that is depending on epoch or place, we cannot judge such act as moral nor immoral. The inhabitants who tell or do not tell where the commander is hidden to the Nazis can be judged moral or immoral as their act will always have a relative significance depending on time and place. Restricting or promoting smoker’s rights is also relative for the same reason. Such acts are just out of scope of judgement in ethics. As for lying to the Nazis, it would be considered immoral as lying will always be intrinsically bad despite that it can lead to good consequences. In the same way, killing, coercing, stealing, betraying, cheating are immoral acts because they will always be intrinsically bad in nature. Unlike them, telling the truth, saving one’s life, feeding the hungry are those acts that will be always be intrinsically good. Here, we can judge somebody’s act moral if it went from intention to action of the same person. A good intention cannot be considered morally good nor morally bad since it is still not a whole act, but a part of it, which is relative. In this case, donating to charities around the world is paradoxically out of scope of ethical evaluation. Even if a donor has good intentions, he or she does not still achieve the wholeness of the moral act. In other words, we cannot be sure about to what kind of action our donations will contribute.

As we see, holistic ethics is not based on the consequence of the act, compared to traditional accounts of ethics. Moral acts of the whole are defined as acts whose intrinsic values are constant and cannot be changed depending on time and place. In this case, the main concern would be to know if a human being is able to define what kind of intrinsic value has an act. How can we know if it is not changed after centuries or it is interpreted differently in other countries? However, this is not about tracing the history of interpretations of a particular act to define if its meaning was constant. A moral act of the holistic realm is already clear from the dubious factors that could change its intrinsic value. If we doubt about its intrinsic value, we cannot judge it moral. A moral act is good without hesitation. Giving to drink to someone who is dying of thirst is a pure moral act. It is good in itself. It does not matter if we are giving to drink to a dying priest or to a dying murderer. An intrinsic value of such act that is saving one’s life was the same and will always be the same through centuries. In the same way, stealing food is a pure bad act even if it is for somebody who is dying of hunger. An intrinsic value of stealing is bad in itself and no consequence can change its value. We cannot say that Robin Hood’s acts were moral when he was stealing from the rich. Even if he was giving to the poor what he was stealing, any good intention or consequence does not make better or change an intrinsic value of stealing. On the other hand, we can judge his separate act of giving to the poor as morally good, even if what he was giving was stolen. Any bad intention or consequence cannot change an intrinsic value of a moral act. Finally, acts whose value can have a double signification depending on intention or consequence cannot be judged from the perspective of ethics. Putting a murderer in a prison is an example of such dubious act which cannot be judged if it is moral or immoral. An action which consists in killing for saving one`s life in the same instance also rules out the possibility of judgement. However, if this act of killing is considered as a separate act, it would be judged as immoral. Even if it is for the sake of saving one`s life later, there are two separate instances to be judged.

It may seem that such approach of holistic ethics imposes limitation on judging the morality of actions. Many specific actions will actually fluctuate between bad and good ones, thus will be ruled out from the judgement as relative in regard to the whole.

This can be explained that a human being can perceive manifestations of the whole in pure moral or immoral actions, while he or she is not capable of perceiving and judging “a grey area” of actions which are questioned in terms of its intrinsic value. In this regard, my attempt was not to replace all the ethical theories with a new account of ethics, but rather to contribute to a new perspective of ethical reasoning related to the whole to solve the problem of classical moral accounts.

Bibliography:

- Kant, Immanuel. Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals in Ethics, Edited by Steven M. Cahn, Peter Markie, Fifth Edition, Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Mill, John Stuart. Utilitarianism in Ethics, Edited by Steven M. Cahn, Peter Markie, Fifth Edition, Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Hegel, Science of Logic, Translated by A. V. Miller; Foreword by J. N. Findlay. London: G. Allen & Unwin, 1969.

- See more about the perception of the whole on https://postulat.org/perception-of-the-whole/